A psychedelic trip can be a powerful, healing experience, but for a small percentage of the population, it can also trigger a big problem: Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD).

“Today’s society is one that talks about psychedelic drugs as a miracle for a bunch of different ailments, but there’s no real chatter about the downsides of these molecules, such as HPPD,” Ehave CEO Ben Kaplan tells Psychedelic Spotlight.

His Canadian digital therapeutics development company strongly believes that some hallucinogenic drug users have a genetic predisposition to develop the condition, which affects around 5% of all LSD users. So, Ehave is launching a 12-month research study that it hopes can identify a genetic cause of the condition.

The goal of this research is to isolate an individual’s risk profile when it comes to consuming hallucinogenic drugs and leverage this data to encourage harm reduction and prevention in clinical trials involving psychedelics.

Kaplan says he was inspired to pivot Ehave towards investigating HPPD after speaking with an individual who suffers from the disorder.

“HPPD is a discomfort. Some people have it for 10, 15, 20 years and they regret the day they did the drug that caused it,” he explains. “We want to try and use DNA and genetic biomarkers to see if a person is predetermined for HPPD so we can tell them that if they want to take a psychedelic drug, this could be the outcome. Today, that information doesn’t exist.”

What is Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder?

HPPD can cause a person to continue reliving the visual elements of an experience caused by hallucinogenic drugs. While some psychedelic flashbacks can be pleasurable, individuals with HPPD instead experience confusing and unsettling visual effects. The disorder can cause functional, social, and occupational impairment, distress, and anxiety.

HPPD was first described in 1954, however, it was not established as a syndrome until 2000. A 2016 study characterized HPPD into two forms: Type 1 which is brief, random flashbacks, and Type 2 where individuals experience perceptual distortions that are chronic over months to years and where the visions vary in intensity.

While the disorder is considered rare, according to two research papers authored in 1982 and 1984, between 5% and 50% of all hallucinogen users are reported to have experienced at least one flashback. Individuals with the disorder also report having recurring disturbances, with symptoms including intensified colors, flashes of colors, color confusion, size confusion, halos around objects, seeing images within images, visions of geometric patterns, difficulty reading, and feeling uneasy.

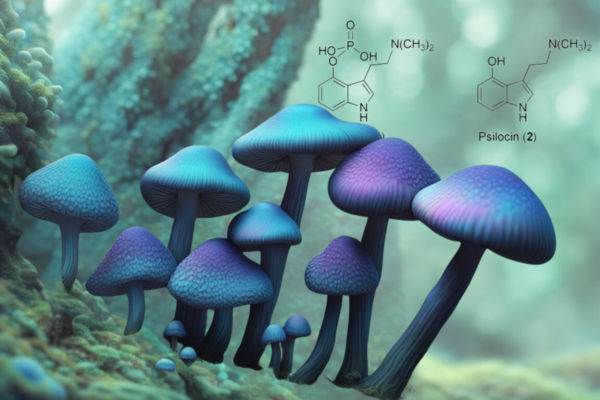

There is no current cure for HPPD, and it is a possibly permanent syndrome. Its risk factors are largely unknown. The exact cause of the disorder is also still a mystery apart from the fact it is linked to the prior use of hallucinogenics. It is not yet understood the type or frequency of the drug that causes the disorder, but according to a 2003 study, HPPD is most commonly linked to the use of LSD. It can also be triggered by using psilocybin (found in “magic mushrooms”), MDMA, cannabis, psychostimulants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a drug commonly prescribed to treat depression.

There is currently no standard treatment for HPPD. SSRIs are known to worsen the symptoms of HPPD when used as a treatment for the disorder. Other drugs prescribed for HPPD include anti-seizure and epilepsy medications, but neither of these has proven effective for most patients.

Isolating HPPD Risk Profiles

Kaplan tells Psychedelic Spotlight that Ehave’s year-long study, in partnership with an unspecified global university, will involve 3,500 participants over three stages.

The first stage of the study will involve developing a battery of visual tasks that cover a broad assessment of optical processing. The 30 to 45-minute test will include questions about HPPD symptoms and other mental health issues. Through a web portal, participants will be able to access and complete the test remotely, facilitating the recruitment of approximately 100 participants with HPPD and 100 control participants.

The second stage will involve the recruitment of a larger pool of participants of approximately 1,000 participants with HPPD and 1,000 control participants that will each submit genetic samples via a test kit. The analysis of 200 participant samples will result in a report. Finally, the third stage of the study is the development of a web-based test platform and the commercialization of a genetic test for HPPD susceptibility.

Kaplan explains that Ehave’s goal is not to find a cure for HPPD but to offer a person considering taking a hallucinogenic drug the ability to make an informed choice. “It’s an additional tool to give a person so they can weigh up the risk versus reward,” he says. “Any tool that someone has to evaluate a drug they are going to put into their body for any reason that is available is powerful. Where the cure comes in, we will leave that up to drug development companies.”

“There’s a dual path here,” Kaplan adds. “One is the non-profit side which is helping people with HPPD. The other side is the for-profit which is trying to stop people from getting HPPD by giving them the science that can tell them if they are predetermined to develop the disorder.”

Improving Clinical Trial Participant Safety

Kaplan says he hopes if Ehave is successful in its research, drug development companies could use its genetic test for HPPD to improve clinical trial participant safety. “Today, many companies are going through clinical trials and 5% of participants could develop HPPD,” he says. “Since there’s no cure for HPPD, these companies go about their routine of testing new drugs on humans to try and get Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, and HPPD has probably hit them in the face a few times in their trials.”

“Large companies like Compass Pathways could be our customers in the future because they could use our biomarkers or testing to decide if they should include or exclude a person from their clinical trial. What we are trying to do is not hurt the industry but give drug developers another tool so they can excel quicker.”

![MindMed Management Update & Earnings Call [ MMED / MNMD / MMQ]](https://psychedelicspotlight.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/maxresdefault-135-600x338.jpeg)