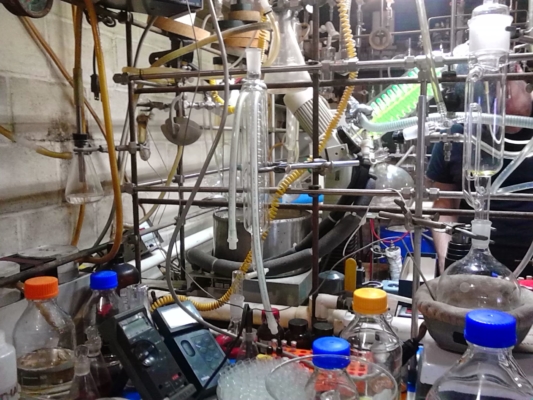

Thirty minutes east of Oakland, overlooking Mount Diablo, there is a hobbit hole dug into the side of a Pleasant Hill. It is a modest and unimpressive structure, gilded with a patina of rust and swallowed by English Ivy, but inside this hobbit hole a White Wizard, Alexander Shulgin, has crafted his Alchemical Hideaway. Most evenings the Wizard could be found hunched over his bubblers and boilers listening to string quartets, condensing spirits from aromatic wisps and vapors, occasionally releasing a plume of steam and stench. Around the Wizard sat a tiny cathedral of colored jars, bottles, vials, and flasks, each one holding a potion or powder of unimaginable power. A flask of sweet smelling oil might be a deadly poison or a powerful aphrodisiac, a vial of white powder could be a miracle cure or a pinch of Philosopher’s Stone. Looking at the endless array of jars it is impossible to tell what each substance might do, each vial is labeled with glyphs that only other alchemists can read.

This alchemical hideaway may sound plucked from fantasy, but I assure you it is real. It is the laboratory of the famous psychedelic chemist Alexander Shulgin. This place is fantastical but it is not pure fantasy. This Wizard was more likely to be found in ethnic print shirts than white robes, and the string quartets played through the tinny speaker of a beat-up transistor radio via the local Public Radio station. Other than these few artifacts of the American modern age, this alchemical hideaway could be the timeless lair of any 17th level magic user worth his salt. And in this alchemical hideaway Alexander Shulgin designed, crafted, synthesized, and discovered more psychedelic and psychoactive molecules than any other chemist who ever lived, and perhaps more than any other chemist who will ever live.

Alexander Shulgin’s Early Life

Standing in Shulgin’s lab just days before his death I am struck by a dim sense that Alexander Shulgin, Sasha to his friends and family, might be the last of his kind. At 88 years of age Sasha Shulgin was the last holdout of the American gentlemen scientists, self-employed innovators in the mold of Albert Einstein or Nikola Tesla. These were educated men with the personal fortune to pursue the science of discovery purely for fun. Shulgin was a research chemist unrestrained by corporations or academic institutions demanding results. Free to follow his whim and passion Shulgin was arguably the most prolific psychoactive chemist of the 20th Century, producing dozens if not hundreds of novel psychedelic compounds over the course of his career. Looking over the rows of jars with faded and yellowing labels I can only wonder how long each bottle has been sitting. Some jars hold material synthesized last year, others were set down forty years ago and forgotten, added to Shulgin’s ever-growing list of “I’ll get back to that someday” projects. But Alexander Shulgin’s days of getting back to his alchemical hideaway have come and gone, the bubblers and boilers sit cold and dry, the inscrutable glyphs stare silently across a maze of tubing and glassware. The Great White Wizard lay in the big house dying, those prophetic days would never come.

Legend has it that the Wizard retired to his alchemical hideaway in the late ‘60s, but the story starts long before then. Even as a child Shulgin was a prodigy, his parents were both teachers, musicians, and prolific poets, his focus as a child was always on education. His father was a metallurgist and no stranger to science, but even in a family of poets and academics Sasha was a bit of an oddball. “He had to learn how to tone it down, you know, to be funny and engage people,” says Ann Shulgin, Sasha’s second wife and collaborator of over 30 years. “He knew that if he appeared too smart in front of the other children he wouldn’t be accepted, he would be the boy that no one liked.” But the child prodigy who hid behind playground fart jokes also had an organic chemistry textbook in his backpack that he would memorize in private moments. This was when he was eleven. He was accepted to Harvard on scholarship at age fifteen and dropped out later to join the Navy in the middle of World War II. “He always said he was hypomanic,” recalls Ann. “Just a little below fully manic, so he needed to have all these different projects and new experiences to keep his mind occupied.” To relax he would play the viola or piano, often dropping into Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf” to lighten his mood.

Shulgin returned from the Navy to finish his Ph.D. at Berkeley, then eventually landed a senior research position at Dow Chemical. His commercial success with the biodegradable pesticide Zectran granted him freedom to study whatever he chose at Dow. Shulgin’s primary interest was psychoactive drugs, particularly mescaline, to which he was exposed in the late ‘50s. He was also interested in the rumor that prison inmates were using nutmeg as a psychedelic to get high and wanted to find the active compound. “You have to remember, back then there was a great deal of hope that figuring out these psychedelic molecules would be the key to solving all kinds of mood disorders, insanity, schizophrenia, psychosis, dementia, the whole lot,” says Paul Daley, Shulgin’s long time collaborator and heir apparent to the keys of the Alchemical Hideaway. “Of course we now know it’s not quite that simple, but the laws changed shortly after that and most of the research just ended.”

Shulgin Becomes a Legend

As the legal climate towards psychedelics shifted in the early ‘60s, Shulgin left his position at Dow and retired to his family estate on Pleasant Hill. The Wizard’s beard grew longer and whiter. He played his viola with local string quartets, “Because quartets always need a viola,” says Ann. “It’s an easier position to fill.” And on one of those days he cleared out the old hobbit hole, a brick-walled basement leftover from a building burned to the ground long ago. It was full of spiders and rat turds, but he had a vision, it would be his new laboratory. He began collecting equipment. “He was a scrap hound,” says Daley. “He would collect whatever equipment he could get his hands on. Anytime a local chemical company went out of business or was throwing something out, he’d be in the truck, he would take almost anything. Glassware, chemicals, solvents, propane, precursors… He would take it all.”

Piece by piece the Alchemical Hideaway came together and the Wizard went to work. Late at night the old radio would play symphonies as The Wizard conducted into the air with a glass stirring rod, checking temperatures in reaction vessels, evaporating droplets of colored liquid into clear dishes of oils, salts, and waxes. And then, when a pinch of Philosopher’s Stone was properly washed and dried, into a little brown bottle it went. A cryptic glyph of a molecule was scrawled on a label and taped to the front, and these little drawings soon became known as Shulgin’s “Dirty Pictures”. And when a new dirty picture appeared it was tested, first on Shulgin himself in small doses, and then on a trusted research group of friends. The results were sometimes disappointing, and the results were sometimes spectacular.

Because of a friendly advisor relationship with the DEA, Shulgin was able to obtain a Schedule I research license which allowed him to synthesize, possess, and test new psychoactive drugs on himself and others. It is impossible to overstate how much of a pioneer Shulgin was in this field. “There are dozens of active and inactive compounds in cannabis; terpenes, cannabinoids, and so on. We take all this stuff for granted today,” says Kenneth Morrow, founder of Trichome Technologies and expert on cannabis terpene extraction. “But Shulgin wrote the first paper on this back in 1971.” Back in those days there was a grove of pot plants in the Wizard’s back yard. The government issued Shulgin marijuana tax stamps so he could legally grow cannabis for research purposes. “Today the cannabis market is obsessed with isolating cannabinoids for medical purposes, and here Shulgin was doing this research forty years ago!”

Shulgin’s Decades of Psychoactive Research

Although Shulgin never met a psychoactive plant he wouldn’t explore, he was not fond of smoking marijuana. “He didn’t really get along with pot,” says Ann, who shared a similar dislike of the experience. “He just thought, you know, what’s the point of sitting around being stoned all the time. He didn’t think there was much to be learned from the experience.” He had a similar feeling about the dissociative hallucinogen Ketamine. “He really didn’t like being that disoriented,” says Ann. “He was always looking to learn something from the experience. He was looking for a teacher to show him something.” Shulgin’s favorite drug was LSD, and though he was accustomed to taking carefully measured 300 microgram doses, he could still be knocked off guard. “There was one batch we got that was just a little more potent than we were used to,” says Ann. “We did our usual dose but for some reason it came on so strong we were not expecting it. Sasha was going from room to room locking all the windows in the house, afraid he would not be able to function later on. Why he was locking the windows I don’t know,” she says with a laugh. “But we were both pretty surprised by that one.”

Ann and Sasha often experimented with psychedelics together, and shared their findings with their confidential research group. “Different people have different body types, so Sasha thought it was important to see how a drug reacts in all kinds of people.” When I ask Ann what Sasha’s favorite of his own chemicals is she knows immediately. “It would have to be 2C-B. He was always very proud of that one. He called it the Great Teacher. Although I preferred 2C-B-Fly a bit more.” But there are so many to choose from. DiPT, 5-MeO-AMT, 5-MeO-DALT, Methylone, 2C-T-7, and this list goes on. Ann can’t say for sure how many trips they shared together, she just smiles and says, “We stopped counting at around two-thousand.” This is a mind-boggling number considering the total may actually be closer to four-thousand.

When pressed to reveal elements of Sasha’s darker side or other experiences that were frustrating Ann pauses and thinks. “He was not a perfect man. He could get moody and stop talking, the communication would stop.” I ask for an example. “Well,” she thinks for a moment, “You could tell Sasha was in a bad mood if he was cleaning something. If you saw him in the kitchen washing the dishes you could be sure there was something really bothering him and you’d better stay out of his way.” Paul Daley confirms that Sasha was the same in the lab. “If he ever hit a sticking point or couldn’t figure out why something wasn’t working, he would begin breaking down the lab and cleaning things. He’d clean the glassware, the tubing, scrub it all out. And by the time he was done cleaning and setting up he’d have thought of two or three more things to try, or eleven.”

Although Shulgin worked with many types of drugs his favorites were the phenethylamines, psychedelics that were more sensual than overpowering. Ann recalls a time she and Sasha tried the psychedelic brew ayahuasca with a local circle. “Sasha had a hard time with that one. I don’t think he liked all the different stuff going on, and it just didn’t agree with him.” Whether it was the constraint of the ritual, the bitterness of the tea, the nausea, the heavy hallucinations, or the whole combination, Ann says it wasn’t for them. “We tried to finish the ritual, which required taking a second dose, so we took a smaller dose and tried to ride it out.” Ann remembers very clearly it did not go well. “Sasha had had enough by that point, and later in that trip I heard a spirit or a voice in my head telling me, Don’t come here again.”

The DEA Raid and the End of an Era

Shulgin’s golden era of unfettered psychedelic exploration went on for over two decades, his discovery of new chemicals climbing into the hundreds. “He was very proud of his Schedule I DEA research license,” recalls Daley. “It was the first thing he showed me when I arrived at the lab in 1977. It was pinned to the wall right inside the door. He just pointed at it and smiled.” That little golden ticket gave the Wizard the power to work his magic without interference. Shulgin had always had a good relationship with the DEA, he was one of their experts, he was the expert, he even taught seminars and wrote law enforcement reference documentation. But his relationship changed in 1991 after he wrote PiHKAL, a large chemical reference of his discoveries in the phenethylamine family of psychedelics, including his star creation 2C-B. The psychedelic community saw PiHKAL as a groundbreaking work of great importance, the law enforcement community viewed it as a clandestine cookbook. Shulgin was no longer the DEA’s exclusive expert, he was everybody’s expert, and the DEA didn’t like that.

The DEA finally decided to revoke Shulgin’s Schedule I license in 1995, and this action came in the form of a raid on the Alchemical Hideaway, an event now known as the “Great Unpleasantness.” Police and federal agents drove up the Pleasant Hill and stormed into the hobbit hole with search warrants and a decontamination unit. They were stunned to find hundreds of brown jars labeled with dirty pictures that only other alchemists can read. They were also stunned by improper storage, improper ventilation, improper bookkeeping, general clutter, messiness, and other environmental code violations that led to the removal of Shulgin’s license. “Sasha says he gave the license back,” says Daley, “But that may be a technicality, or a point of pride. However it went down, they were there to take it from him.”

Things changed at the hobbit hole after that. Research continued but at a slower pace, and research with scheduled chemicals was now strictly forbidden. Dozens of tiny jars and vials containing scheduled chemicals were removed and destroyed, replaced with gaudy pink straws marking their absence. The Wizard went into a funk, he could no longer practice his magic, not in the unfettered way he used to. He had to work ahead of the law, around the law, find chemicals the law didn’t know about yet, things that were still technically legal but would soon be illegal. He continued to share and publish his research, he watched Chinese labs make fortunes from his inventions weeks after his research went public. He privately fumed at the DEA, but he kept quiet and kept his head down. The Wizard was an old man, he did not want to spend the rest of his life in court or in jail. Just like on the playground as a child, he had to tone it down or get beat up by the bullies. Brilliance always makes any easy target.

Alexander Shulgin Near the End

The last time I saw Sasha was five days before his death. He was in a wheelchair, almost deaf, almost blind, suffering from dementia, and had developed liver cancer on top of everything else. I told him I came all the way from Seattle to see him, he kept asking, “Why? What for?” He is almost entirely out of breath. I can’t tell if he is confused or just playing with me, but it feels like he’s reaching for the energy to make a joke. Even at death’s door, always with the jokes, the constant corny jokes. I remember the first time I spoke at length with Sasha, sitting in an Italian restaurant after a psychedelic conference in San Jose. A young chemist sat next to me asking all kinds of questions about chemistry, and Sasha only wanted to make jokes —or worse, puns. “What’s the best time to go to the dentist? Tooth-hurty.” Sasha would torture people with an endless barrage of these groaners, probably from a book of jokes he memorized as a child. “He was relentless with the dirty jokes,” recalls family friend Greg Manning, who spent a magical evening driving around Burning Man in a golf cart with Sasha and Ann. “I kept telling him to stop and he kept nailing me with one-liners. I was laughing so hard I could barely breathe. He was just destroying me.”

Sasha couldn’t summon the energy to make that last joke. I said goodbye and thanked him for everything he had given to the world. He died a few days later at age 88.

It’s hard to say what life will be like on Shulgin farm now that the Wizard is gone. Although Shulgin’s published work is well known, there are still volumes of unpublished notes that have never been transcribed. “There are dozens of Sasha’s journals in storage,” says Tania Manning, Shulgin’s archivist. “We’re still in the process of cataloging everything.” Tania takes me around the estate and shows me all the plants in the Wizard’s magical garden. Back in the hobbit hole Paul Daley keeps the equipment clean and occasionally fires things up to continue Sasha’s work. “I think there’s still great value in researching the duds,” says Daley, referring to the many Shulgin chemicals that should be psychoactive but are inactive. “These chemicals appear to have no psychedelic effect but may have all kinds of secondary effects that have never been explored. These could be fruitful lines of research. The exploration in this area has barely started.”

Shulgin already holds many chemical patents and who knows what else is hidden away in the unpublished notebooks. Those around Shulgin have formed the Shulgin Research Institute (SRI) to preserve his research and carry it into the future, but it’s hard to imagine that Shulgin’s independent and imaginative style can ever be preserved by a foundation. Many people think of chemistry as something technical and boring, but Shulgin never thought of it that way. “I’m just a cook,” he would often say, and from the look of the Alchemical Hideaway, Shulgin liked things messy and exciting.

I remember watching Sasha and my chemist friend scrawling dirty pictures on a napkin in the Italian restaurant. They each drew a series of synthesis pathways from one molecule to another, trying to outdo each other. “It’s so amazing,” I say looking at the napkin. “Adding and removing atoms from existing molecules turns them into totally different molecules. It’s like you’re rearranging the fabric of reality.”

“That’s it exactly,” replied the Wizard, peering at me under a bush of crazy white eyebrows. “It’s the closest thing we have to real magic.”