It is well known that ingesting LSD can cause wild and out-of-this-world experiences. From hallucinations to feelings of oneness with the universe, even those who have never experimented with the mind-altering substance are aware of its power.

Perhaps less well understood, though no less fascinating, is the tale of how LSD was first introduced to humanity. This is a story of scientific ingenuity, self-experimentation, war, and a new medicine.

Chapter 1: Discovery

Our story begins in 1938, a year before the world was destined to once again descend into chaos. In the picturesque Swiss town of Basel, a young and unknown chemist named Albert Hofmann was diligently working for Sandoz Laboratories, a pharmaceuticals company.

Hofmann’s task was to synthesize chemicals found in the ergot fungus, or create related novel compounds which may be medically useful in one way or another. He had already created 24 such compounds, experimenting by combining the chemical starting point for ergot —lysergic acid— with other organic molecules.

Having so far failed to discover a useful medicine, Hofmann created the 25th variant, this time bonding lysergic acid with a molecule called diethylamine. And thus, lysergic acid diethylamide-25 was born, now commonly referred to as LSD-25, or simply LSD.

Unfortunately, when the 25th variant was originally tested in animal subjects, in Hofmann’s words, it “aroused no special interest in our pharmacologists and physicians.” This was despite the fact that the animals who had taken the substance acted strangely and became hyper excited.

LSD-25 was therefore shelved, being “apparently useless.”

Despite moving on in his research —after all, there had to be an LSD-26, LSD-27 and so on— something he saw in the animal trials for the 25th variant stuck with Hofmann. He had a “feeling that this substance could possess properties other than those established in the first investigations.”

Chapter 2: Self-Experimentation

Years later, on April 16th, 1943, as the horrors of industrialized warfare surrounded neutral Switzerland, on a whim Hofmann decided to again synthesize the substance. It was then, in an act of fate, that he accidentally absorbed a miniscule amount of LSD through his skin.

This would go down in history as the world’s first LSD trip.

Writing years later, in his book LSD: My Problem Child, Hofmann recalled that during this time he “perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.”

Despite the experience lasting only two hours, Hofmann was amazed at the power of his creation. And like any good scientist, he knew exactly what he had to do: self-experiment.

Three days later, on April 19th —a day that would forever be remembered by psychonauts across the world— Albert Hofmann purposely dosed himself with LSD-25.

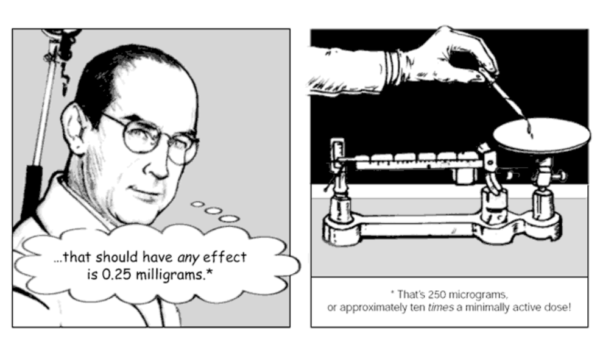

Of course, Hofmann wanted to be as responsible as one could possibly be while ingesting experimental mind-altering drugs, so he decided to take a very small dose of 250 micrograms. In other words, Hofmann took only 0.00025 grams (250 millionths of a gram!) of LSD-25, which he hoped would be enough for a threshold dose —the minimum needed amount to feel slight perceptual changes. Despite this hope, he expected to feel nothing.

COMIC CREDIT: Courtesy of Jon Hanna LSD and Psilocybin Research

Unfortunately for Hofmann, LSD-25 was more potent than he could have imagined. That 250 micrograms, as we now know, was roughly 10 times the size of a threshold dose!

Unable to properly function, Hofmann had a lab assistant escort him home. As the war had caused gasoline to be rationed, no cars were available, and Hofmann had to return home by bicycle.

To his amazement, as he peddled through the streets of Basel, everything in his “field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror.” Forever after, April 19th would be memorialized as Bicycle Day to commemorate the discovery of LSD.

By the time he got home, Hofmann feared he was losing his mind or even dying. To make matters worse, his female neighbor had transformed into a “malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.” Clearly, something was wrong.

He called a doctor, but other than dilated pupils, his physician could not find anything wrong.

Eventually, perhaps accepting his fate, “the horror softened and gave way to a feeling of good fortune and gratitude.” Describing the experience, he would later write that “I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange.”

The next morning, Hofmann woke feeling “refreshed, with a clear head,” and with “a sensation of well-being and renewed life… Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure… the world was if newly created.”

Chapter 3: LSD Becomes a Medicine

After completing further animal tests to ensure that his “wonder drug” was indeed safe, Hofmann continued to experiment on himself with LSD-25.

He did this, not publicly with his employers, but rather secretly with the help of two close friends. At the time, his main goal was “to investigate the influence of the surroundings, of the outer and inner conditions on the LSD experience.” In other words, he was pioneering the concept of set and setting.

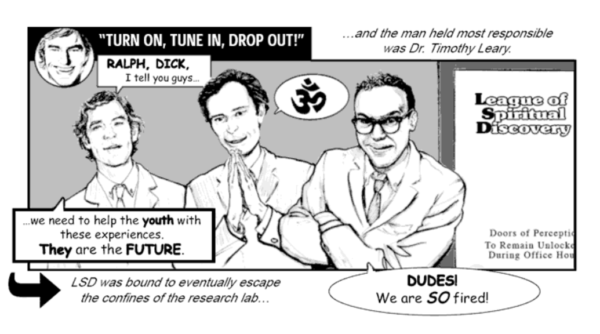

Eventually, after discovering the therapeutic potential of his creation, Hofmann shared his secret with researchers and scientists. By the 1960s, LSD was being seriously researched as a treatment for a range of mental health conditions, from anxiety to depression, schizophrenia, alcoholism and more.

By 1965, 40,000 patients had been prescribed LSD, and more than 1000 papers had been completed on the matter. In one study, 40-45% of severe alcoholics remained abstinent for a year after taking LSD.

Unfortunately, LSD had also escaped the lab and was being used widely in the counterculture and by anti-war activists. Due to this, a political campaign was launched against the mind-expanding substance, and LSD became viewed as a danger to society, corrupting the youth. Despite the promising clinical evidence that it could be used as a medicine, in 1968 the Nixon regime made LSD and other psychedelics illegal, halting most scientific progress.

This ban pushed back the study of LSD by decades, and it wasn’t until the mid-2010s that serious research into the substance began picking up steam. In 2014, a small MAPS-sponsored study once again found therapeutic benefits to LSD, which opened the floodgates. Today, there are dozens of ongoing clinical trials looking into LSD as a treatment for everything from depression to migraines.

In the most recent study, LSD was administered to treat anxiety disorders. Amazingly, the study found that 65% of patients saw anxiety levels drop by at least 30% from where they were before treatment, even up to 16 weeks after dosing. In a twist of fate, this study was also conducted (at least in part) in Basel, Switzerland.

If these impressive clinical results can be replicated, then it is only a matter of time before Hofmann’s “problem child” once again is used widely as a medicine.