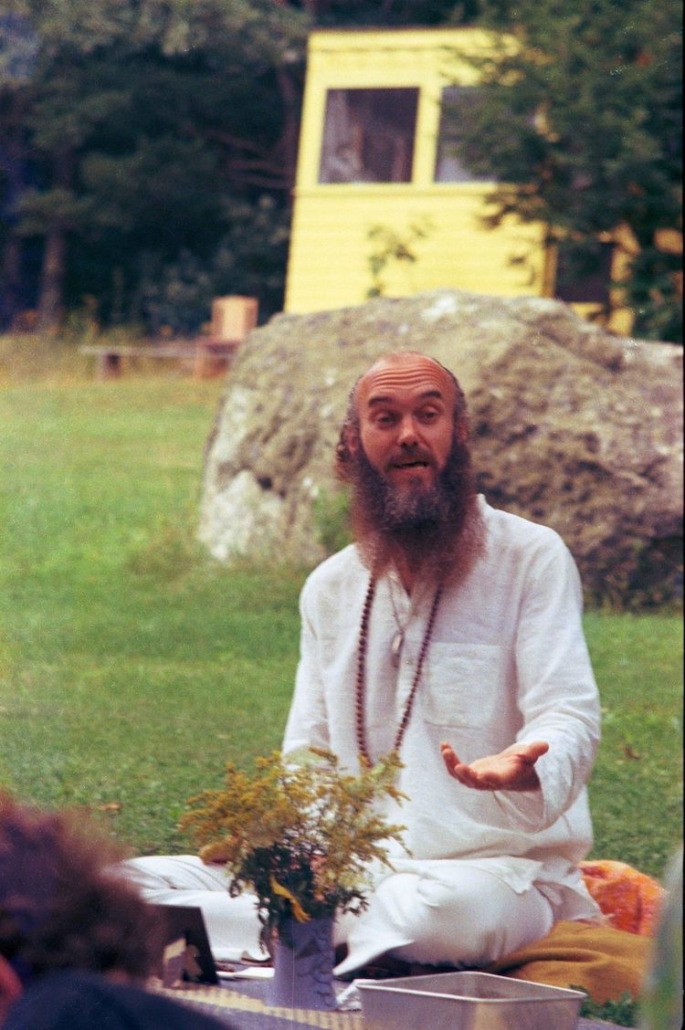

One of the most famous proponents of the ‘60s psychedelic movement was researcher and former Harvard professor, Richard Alpert, who later became the spiritual teacher Ram Dass. A few years after pioneering some of the first academic studies with LSD and psilocybin, Alpert went on a spiritual journey to the Indian subcontinent. He studied with Neem Karoli Baba, a Hindu guru who taught many students from the States seeking salvation, and gifted Alpert with his new name and new path.

Dass devoted the rest of his life to bringing the knowledge he gained from his time in India back to the US. He died in 2019. Since then, meditation and Eastern spiritual traditions have permeated psychedelic culture in the West. But researchers are still puzzled by the similarities between meditation and psychedelics. Dass certainly demonstrated that a psychedelic experience may propel someone to become more interested in meditation, but why?

Recently, a paper published by Jake Payne and other researchers from Monash University argues that meditation may be a powerful tool in any psychedelic therapists’ arsenal. That is, meditation should be used to maximise the clinical potential of psychedelic treatments.

The Problems with Psychedelic Therapy

Over the past ten years, there has been a spike in interest in the use of psychedelics to treat mental health issues. From psilocybin for end-of-life anxiety, to ketamine for major depression, psychedelic researchers are yet to discover the limits of these compounds.

However, psychedelic therapy is an intensive protocol; psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy often comprises one to three ‘dosing sessions’, with the drug being administered in a safe and comfortable space alongside the presence of one or two therapists to act as guides for the trip. These dosing days are sandwiched between preparatory sessions — to ensure the patient is sufficiently ready to take the psychedelic plunge — and integration sessions in order to allow the patient to incorporate any lessons from the psychedelic experience into their daily life.

In their recent paper, Jake Payne and his colleagues argue that this intensive protocol is difficult to implement for a wide population. Multiple clinicians are required in this lengthy intervention, making it economically costly for patients to access psychedelic therapy, or (ideally) for governments to fund them. They also highlight that the psychedelic trip itself can be punctuated by challenging experiences, such as intense anxiety, which may counteract the therapeutic benefits. The researchers therefore suggest that meditation may serve as a spiritual supplement, allowing patients receiving psychedelic therapy to experience the maximal benefit.

The Mindfulness Revolution

Meditation is a multi-faceted concept; there are hundreds of different styles and practices, each contributing to a specific goal. To simplify things, we can define meditation as a deliberate practice with the intention to gain insight into the inner working of the mind, enhance attention, or regulate your emotions. The most common is mindfulness of breathing, where your awareness simply rests on the breath.

It’s no wonder that Ram Dass was so intrigued by contemplative practices; the experiences that people have under a high dose of psychedelics can be strikingly similar to those experienced during deep meditative states. One fundamental similarity between the two is the loss of a sense of self. At the peak of a psychedelic experience, it’s relatively common for an individual’s self-concept to dissolve into nothing, a term called ego dissolution. This insight, that no permanent and unchanging self exists, is one of the long-term goals of meditative practices (dubbed Anattā, meaning ‘non-self’ in Pali).

Another similarity is found in their positive therapeutic effects — as we’ve seen, psychedelics are being touted for their potential in treating an array of mental health issues. Meditative practices have also shown effectiveness in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety, especially when embedded into therapeutic protocols such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Psychedelic Synergy

Despite the positive effects of meditation, Payne points out that starting a practice is extremely difficult (novice meditators are always dumbstruck to see their mind constantly drift off). Moreover, these deep states of meditation related to psychedelics are reserved for practitioners that have devoted thousands of hours to the process. However, as mentioned, it’s argued that embedding meditative practices into psychedelic therapy may provide a more complete and effective intervention.

This perspective is based on a couple of studies conducted that sought to validate the synergistic effects of psychedelics and meditation. In 2019, Lukasz Smigielski and colleagues at the University of Zurich gave either placebo or psilocybin to practitioners on the penultimate day of a 5-day meditation retreat. After the participants received their psilocybin or placebo, they were asked to engage in their usual 6-hours of meditation practice for the day.

They found that the meditators who received psilocybin entered deeper meditative states, experienced higher levels of positively-valenced disruptions in sense of self, and greater positive changes in behaviour and attitudes four months after the retreat, compared to the meditator’s who received the placebo. In other words, meditation enhanced psilocybin’s positive effects.

In a related study, researchers at Johns Hopkins found similar synergistic effects. Within their study, they gave psilocybin to groups that had differing levels of spiritual support. They found that the participants receiving the highest level of spiritual support engaged with spiritual practices (such as meditation) significantly more than the other groups. They also found that this group had a higher sense of life meaning, as well as greater positive changes in behaviours and attitudes six-months after the psilocybin dosing session.

Based on these studies, Payne and his colleagues propose that meditation can help address the limitations of psychedelic therapy, and vice-versa. They use the analogy of psychedelics as a compass, and meditation as the vehicle: “the Compass of psychedelics may serve to initiate, motivate, and steer the course of mindfulness practice; conversely, the Vehicle of mindfulness may serve to integrate, deepen, generalize, and maintain the novel perspectives and motivation instigated by psychedelics.”

Could this perspective spur more clinical researchers to investigate their synergistic effects even further? Ram Dass would certainly be pleased to know about the bright future that may lay ahead for both psychedelics and meditation.