“I wanted to make something with substance, a meaning, purpose, and cultural relevance.”

James Drayton, the producer of Toronto’s first (and only) large-scale psychedelics-based art show, stands proudly in the front lobby of his creation, held in the beautiful and old Lithuanian House on Bloor Street West.

This is the true meaning of the psychedelic renaissance –a loud and proud endorsement of learning about psychedelic substances, their history, their functions, how they work and how they make you feel.

The exhibit is larger than the ads and social media posts let on. An all-immersive experience starts in a clinic –“The new set and setting”— complete with a couch, two comfortable chairs, a plant, and an overall neutral, pleasant atmosphere. Walking through the exhibit’s first floor takes you on a maze of a journey. It starts at the very beginning, with psilocybin mushrooms and their ancient past, telling the viewer that, throughout history, humans have always wanted to “tinker” with consciousness.

The show introduces the “Bee-Faced Mushroom Shaman,” a mysterious figure found in Algerian cave paintings whose body is covered in what suspiciously look like mushrooms. Who was this man? Was he a guide? A vision? A costume? At this time, we can only guess and speculate, but this sets the tone of curiosity for the rest of the exhibit: How long have humans had a relationship with psychedelics? And how deep does the connection run?

From Toronto-based artist Casey Watson’s “Shroom Room” (she says her favourite mushroom is the smallest one– if you’re in there, try to find it!) to The Clandestinos’ blacklight peyote experience hallway, the exhibit is definitely as immersive and experiential as it promises, with plenty of opportunity for both cool photos and learning.

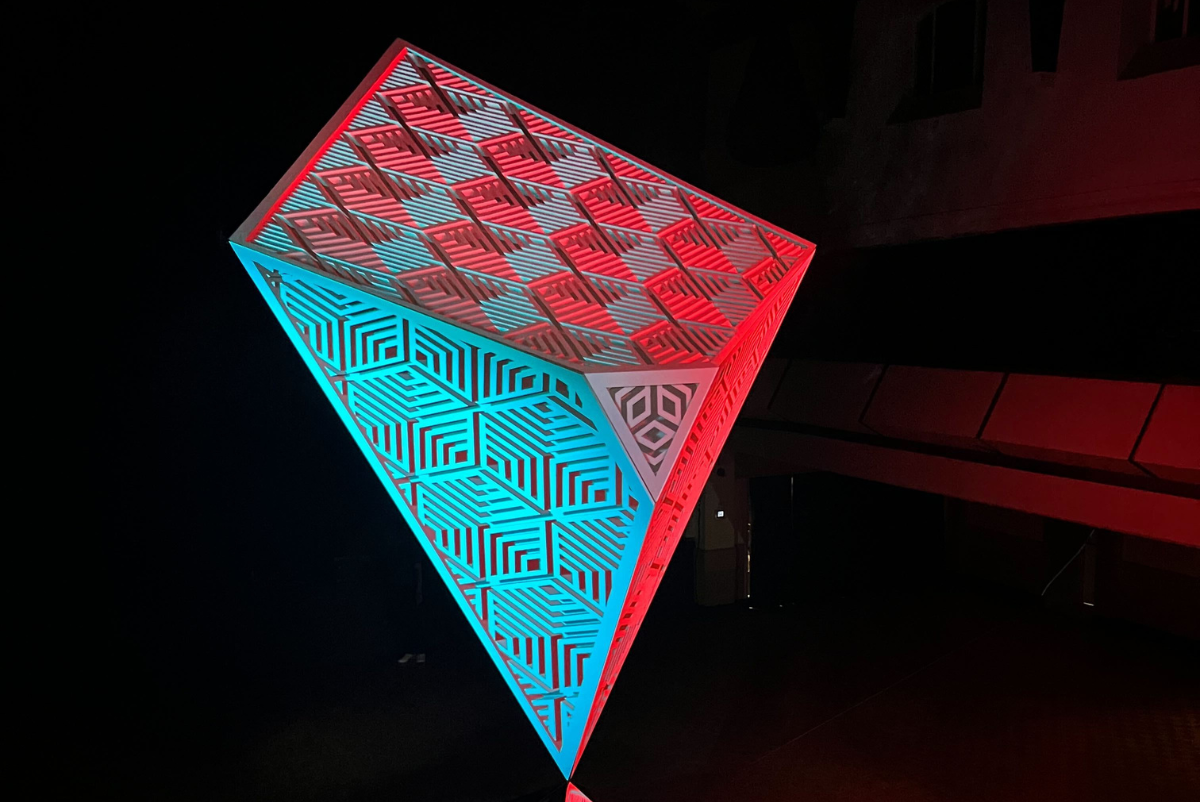

The crux of the exhibit is GMUNK’s massive light show sculpture installation, The Totem, truly bringing together the vision that James Drayon has for the show being at the “intersection of art and technology.” The Totem offers a nine-minute sequence of songs, sounds, and a mapped light and laser experience that can be experienced from the front and the back. California-based Robert Malone, the sound artist that GMUNK worked with for the piece, brought genuine field recordings of real birds and animals. The 25 artists featured in the show were selected and curated through Drayton’s own network and come from all over the world: “I shared the idea and some people got it, and some people didn’t,” says, and clearly, the ones that “got it” were welcomed to be part of it.

A joyful offering for folks in all stages of their psychedelic journey, functioning as a both a museum and an exhibit as well as an adult playground (though kids are more than welcome), the Psychedelics Show is a pleasant introduction for folks curious about psychedelics and a somewhat new perspective to those who already know. For those who haven’t experienced DMT, for example, the simulated trip video offers a realistic experience. One can imagine themselves transported to a psychedelic new realm while still fully in control– and with the opportunity to leave at any time.

A standout piece is a DMT-simulating video piece from California-based artist and motion designer Burt Vera Cruz.

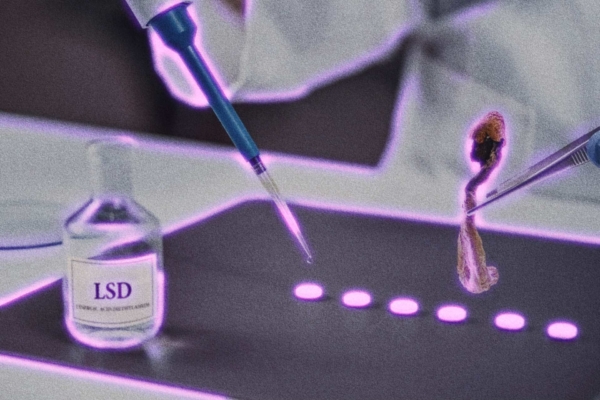

The written content of the Psychedelics Show is Psychedelics 101, but that doesn’t mean it’s not relevant to the experienced user. After all, few can say they’ve really tried “it all,” and the exhibit works to introduce a multitude of the world’s psychedelics and their functions. There’s information on ayahuasca, peyote, LSD, and more, all accompanied with art to represent the substance of choice.

Remembering Maria Sabina

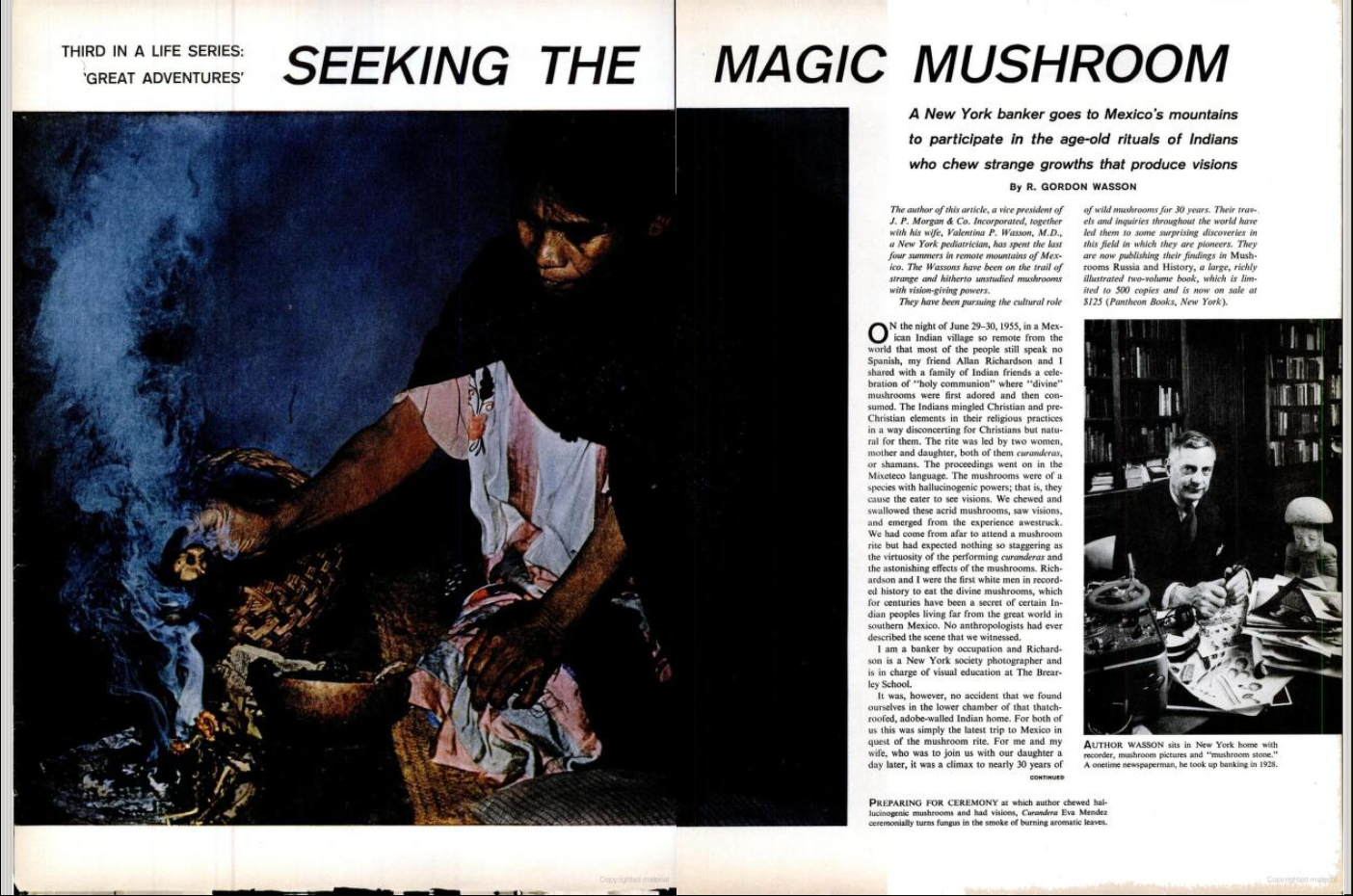

A section on psilocybin, perhaps the most commonly used and best-known psychedelic in the space, has the famous May 1957 Life magazine article and photo essay, “Seeking The Magic Mushroom,” written by R. Gordon Wasson about his trip and stay in Mexico in 1995, where he took psilocybin mushrooms for the first time in a Mazatec healing ritual, called a velada and previously only used to help find missing people and items.

The article describing the velada and the experience and hallucinations, as well as the bright, beautiful, and bold photographs that came with it, brought psilocybin mushrooms to a wider audience for the first time, and Wasson is often credited as being one of the first to popularize magic mushrooms in America. Wasson and New York photographer Allan Richardson became, according to Wasson, “the first white men in recorded history to eat the divine mushrooms.”

However, the article, and the accompanying written text at the exhibit, fails to mention the long-term effects of Wasson’s experience and his article, or Maria Sabina at all. So what really happened at the ceremony? And what happened to Maria Sabina after Wasson took the medicine of the mushrooms and brought it to the West? The truth? Wasson lied to gain access to the velada, claiming that he was worried about his son back home and wanted information on where he was; he later revealed the lie.

The velada took place in Oaxaca, Mexico, under the guidance of curandera (a female shaman or medicine woman) Maria Sabina in her hometown just outside of Huautla de Jiménez. The article describing the velada and the experience and hallucinations, as well as bright, beautiful, and bold photographs, brought psychoactive mushrooms to a wider audience for the first time, and Wasson is often credited as being one of the first to popularize magic mushrooms in America.

Wasson’s article reached millions, and, just under a week later, Wasson’s wife, Valentina Pavolva, published a first-person account of the research expedition in Mexico which was published on the cover of This Week, a Sunday magazine insert that reached almost 12 million readers.

These articles collectively gathered a lot of interest, especially in the hippie and beatnik movements that were blossoming at the time. Author Tom Robbins claims that Wasson’s article was directly responsible for turning himself and a lot of people on to the mushroom movement.

While the article was massively successful and sparked major curiosity and interest in the Mazatec ritual, culture, and psychedelic mushrooms as a whole, it ended up proving to be horrifically disastrous for the Mazatec community and Maria Sabina herself. The community was overwhelmed with visitors who wanted to try the mushrooms and experience the hallucinations Wasson talked about for themselves, and Sabina attracted the attention of the Mexican police, who thought that she was selling drugs to foreigners.

The social dynamics, infrastructure, and relations of the Mazatec community were altered significantly as a result of the unwanted (and unwelcome) bouts of massive attention, and threatened their sacred, and, for so long, secret ritual around the mushrooms. Sabina was blamed for wrecking the community and ostracized, becoming a social pariah in a society where she was once revered as a medicine woman. She was briefly jailed, her son was murdered, and she died in poverty and suffered from malnutrition in her later life, expressing regret over having introduced Wasson and his companions to the mushroom medicine.

The story is tragic, but unfortunately not unique– stories of colonization and exploitation of different cultures from the Western world, repackaged and presented as “discoveries” are common –from tea to spices to drugs. It’s important to be aware of these histories when discussing psychedelics, especially now, as the psychedelic renaissance sees a high percentage of white folks with money at the top directly benefiting from the medicine that other cultures have spent centuries studying and cultivating. This is something lacking in the exhibit: No matter your journey with psychedelics, it’s important to acknowledge where they came from and who really initiated the discoveries, who studied them, who helped pioneer these medicines. While the show alludes to historical hallucinogenic use in the beginning with the Bee-Faced Mushroom Shaman, it’s not continued fully in the rest of the exhibit.

Now, it’s important to understand that not all information can be conveyed fully in limited text and space, and the Psychedelics Show is, of course, working with a limited canvas. Ultimately, the show is there to fulfill an ultimate goal: To educate and inspire, and it piques enough curiosity at the tip of the iceberg to encourage passionate learners to dig deeper after visiting.

Overall, the Psychedelics Show is a pleasant experience for visitors young and old. In town until at least December, but hopefully longer, it should be a necessary stop on any Toronto art-lover’s list. It fills all of James Drayton’s wishes for it: It’s timely, it’s necessary, and it’s relevant. Shows like this remind us of a time that we are lucky to be living in: The psychedelic renaissance is here and now.