What if you could isolate the brain from external stimulation? Create a soundproof space where someone could float in solitude and confinement, and near-absolute sensory deprivation, for long periods of time. Could that person fall into an altered state of consciousness? Peer into the innermost spaces of their mind? Climb deeper into their imagination?

That was John C. Lilly’s wonder in 1954, while employed at the Public Health Service Commissioned Officers Corps. He was a medical doctor trained in biophysics and psychoanalysis. During World War II, he’d investigated the physiology of high-altitude flying and invented instruments that could measure gas pressure. He thrived on research that pushed the limits of the mind. And now he was wondering how sensory deprivation would impact consciousness.

It wasn’t exactly a new area of research. At that time, scientists were exploring the potential benefits psychedelic drugs could have on the mind, especially ones affected with mental health problems. Could an isolation tank have similar benefits, Lilly posed? And if so, what if a hallucinogen were added to the mix?

Lilly decided to find out. He created a dark, soundproof tank, filled it with warm salt water, then blocked out all sound and light. Then he and a research colleague became the first subjects to test out this so-called “perceptional isolation,” first without psychedelics, then later, with LSD.

Floating and LSD

Lilly came from a rather well-to-do family. That, and his controversial experimentations that often raised eyebrows of more mainstream scientists, landed him in the same social circles with notable counterculture thinkers. It wasn’t unusual for folks like Ram Dass, Werner Erhard and Timothy Leary to drop by his house.

In the 1960s, Lilly conducted a series of experiments of his own using psychedelics. Specifically, he floated while tripping on LSD. (He would also use psychedelics in the company of dolphins in an attempt to create a common language between humans and the sea creatures.) Lilly recorded both experiences in his 1968 book, Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer and his 1972 book, The Center of the Cyclone.

“During that first experience with LSD in the tank, I quickly found that it was very easy to leave the body and go into new spaces,” he wrote in the latter book. “The lack of distracting stimuli allowed me to program any sort of a trip that I could conceive of. This freedom from the external reality was taken as a very positive point, not a negative one. One could go anywhere that one could imagine one could go. …I traveled through my brain, watching the neurons and their activities.”

Are isolation tanks still around?

By the time Lilly’s floatation experiments with LSD wound down in 1965, new laws in the U.S. regarding LSD were making it difficult to continue research with the therapy. “Out of the original 210 investigators, there were only six left who were willing and authorized to continue the work,” Lilly wrote.

But interest in the floatation tanks survived. The tanks were reconceptualized as Restricted Environmental Stimulation Technique (R.E.S.T.). And, by the 1970s, commercial tank sales took off. Floating became a popular pastime among artists and those wishing to stretch their spiritual boundaries. Celebrities like Yoko Ono and Robin Williams, and athletes like the Dallas Cowboys reportedly began to float.

Interest stalled in the 1980s, a casualty of the early days of the AIDS outbreak before researchers understood how the virus spread. But in recent years, floating has blossomed with float centers popping around the world.

The tanks vary in size and shape. Some resemble coffins or pods. Others look like submarine chambers. Each are filled with about a foot of water infused with a thousand pounds of Epsom salt. That makes the water so buoyant that you feel weightless, as if you’re floating on top of the water rather than sinking into it. It’s also warmed to body temperature which blocks your proprietary sense of where your arms or legs are in space.

Once inside, you relax in pitch blackness for an hour or so deprived of sound, sight, or touch. The experience has been said to produce an altered state of awareness and, for some, induce hallucinations. At the very least, floaters report a heightened sense of creativity.

“Floatation therapy,” as it’s sometimes called, also claims to have physical and mental health benefits. According to studies, floating in isolating chambers may reduce blood pressure and cortisol levels, reduce lactate levels after intense exercise, and may also help manage anxiety.

Floating has made its way into pop culture, too. The tanks were part of a creepy research experiment in the 1980s sci-fi horror film Altered States staring William Hurt. In the 2003 film Daredevil, Ben Affleck played a blind superhero with heightened senses who used the tanks to get a good night’s sleep. Netflix’s sci-fi series Stranger Things also featured the tanks.

What does floating feel like?

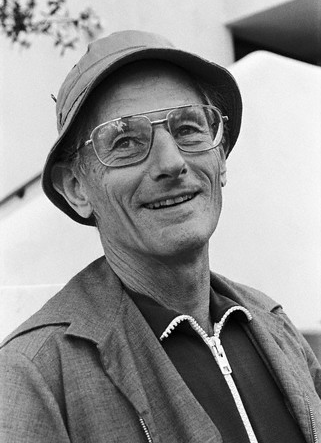

If you really want to know what it’s like to have a sensory deprivation tank-induced hallucination, several journalists have published their experiences. Quantum physicist Richard Feynman in his 1985 book, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! describes it this way:

I had many types of out-of-the-body experiences. One time, for example, I could ‘see’ the back of my head, with my hands resting against it. When I moved my fingers, I saw them move, but between the fingers and the thumb I saw the blue sky. Of course that wasn’t right; it was a hallucination. But the point is that as I moved my fingers, their movement was exactly consistent with the motion that I was imagining that I was seeing.

And, Bri Jurries, A University of San Diego English major, shares her experience in this Huffington Post essay:

After deconstructing myself and the surrounding environment, a feeling that can only be described as pure awareness appeared in the rubble of dismantlement; though I had no idea where I was situated in space, time, and location, I was more aware than ever that I existed, that I was something bigger, larger, more significant, something other than my surface-y, ego-based identity. … I felt persuaded, with strange familiarity, that within myself is the ability to both create and be created, genesis and re-genesis, newness and renewal. I physically felt this conviction deep in my body, a sensation I can only describe as located in the space in the middle of my ribcage. I felt myself drift in the tank, eyes shut, with my long hair extending around my head and purple swirls spiraling above me, I felt divine, like I was God. I am God.