After I was sexually assaulted at 14, I spent the next half of my life trying to forgive myself for that sexual trauma.

The decade after was overwritten by flashbacks, unfurling frustrations, and failed attempts to cement my sexuality. I was either all orgies or all abstinence, vacillating between extremes in every aspect of my life. I was never fine; I was only singing-in-the-street happy or banging-my-head-against-a-California-redwood enraged.

I drove my truck in circles laboring under the delusion that if I could articulate the event perfectly, rendering it with great tact, the memory would lose power. I would be healed and reborn, on top of being re-hymened. I absolutely consecrated myself to the notion that if I wrote something capable of making people laugh, cry and cringe in one tight paragraph, my fingers would ascend from the keyboard, and I would evaporate into a reality where I don’t go home and cry every time the subject of virginity loss is broached over hors d’oeuvres.

When I began to accept that I would never be able to write it perfectly and the concept of catharsis through composition was a little faulty anyhow, I turned toward some more colorful alternatives.

Though I never went into any of my psychedelic experiences with the expectation that they would heal me, I was optimistic that they would allow me to see myself more empathetically. After researching, I understood that psychedelics work on the part of the brain known as the parahippocampal retrosplenial cortical network, which is thought to have a hand in dictating our sense of self –– something that I desperately needed to restructure.

So, I began.

The Clinical Use of Psychedelics May Heal Sexual Trauma

I’ll be honest: my psychedelic-assisted therapy was self-administered. However, while I did have to skulk in dark Scottish alleyways to get the goods, I was obsessive about dosing and “doing it right.” From a consciousness-shifting K-hole in the Whistlebinkies bathroom to shrooms at sunset on Lake Ontario, I found a new sense of softness and empathy for myself with each trip.

When it comes to psychedelics helping sexual assault survivors, my experience is far from singular.

According to Roland Griffiths, a seasoned psychedelic researcher, and professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, over 70% of people who took magic mushrooms to treat mental illness, anxiety about impending death or PTSD cited their psychedelic experience as being one of the most important events in their entire lives. Research also suggests that psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, often induces emotional breakthroughs and profound shifts in perspective for those who ingest it.

A chorus of experts echoes these epiphanies.

My experiece that psychedelics (used safely) are an unrivaled tool to help people access greater embodiment and encouragement to reprocess their trauma and, in the words of sex therapist and psychedelic integration therapist Dee Dee Goldpaugh, “experience a compassionate recasting of ourselves in the story.”

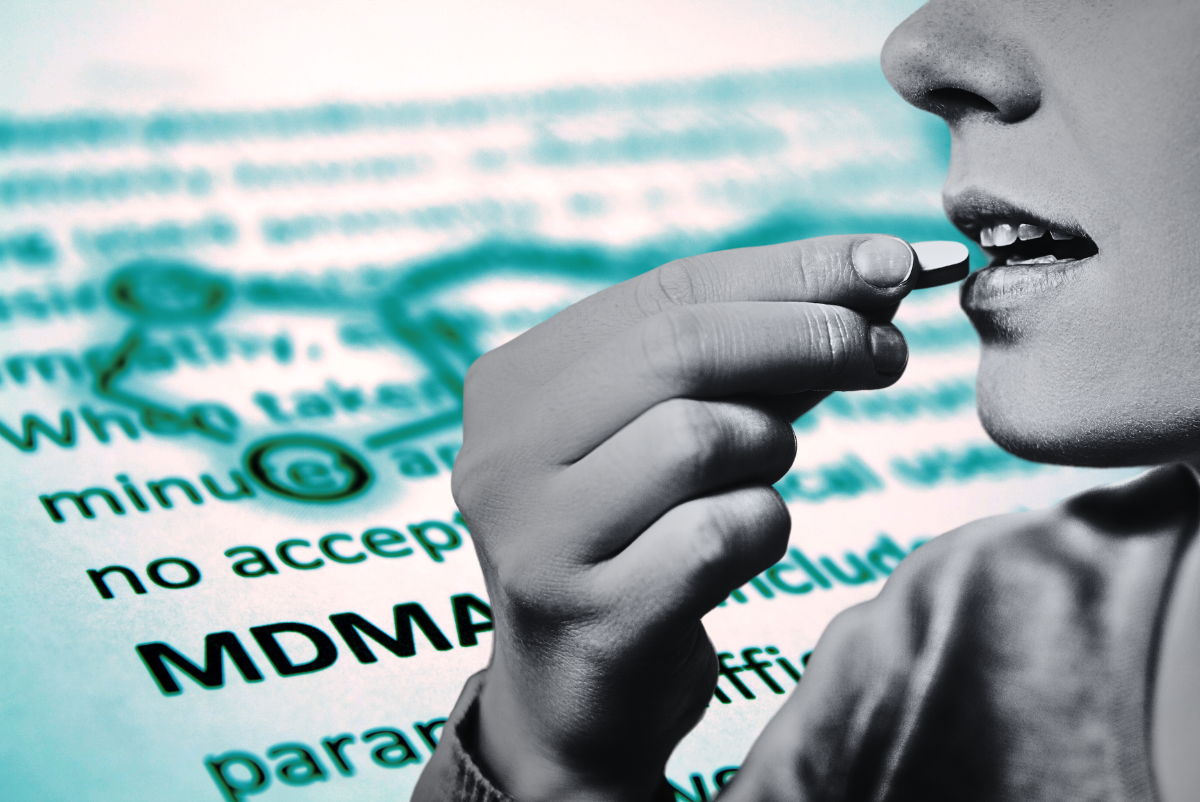

Activist Leia Friedman, host of The Psychologist: Consciousness Positive Radio, gives a glowing review of MDMA: “MDMA is probably the most commonly used medicine for treating sexual trauma, [but] I have heard from different people that ayahuasca, psilocybin, ketamine, LSD, and mescaline-containing cacti were all helpful, as well.”

Similarly, psychologist and sexologist Dr. Denise Renye adds, “Using the psychedelic psilocybin and the empathogen MDMA can both create psychic spaces within individuals to gain a deeper sense of self.” She continues, “MDMA can help an individual recollect a sexual assault without the PTSD symptoms of freeze, fight or flight. MDMA can also allow for the survivor to have a sense of empathy for their self that went through the assault, thus alleviating some of the self-judgement that sometimes accompanies it.”

The evidence isn’t purely anecdotal either; there is a wealth of studies touting the benefits of MDMA for those suffering from PTSD. According to one such study, “after three doses of MDMA administered under a psychiatrist’s guidance, [PTSD] patients reported a 56 percent decrease in the severity of symptoms on average. By the end of the study, two-thirds no longer met the criteria for having PTSD. Follow-up examinations found that improvements lasted more than a year after therapy.”

Looking Forward

It’s not just me. Experts agree psychedelics are an untapped resource in the barbed pursuit of healing from sexual trauma. With the help of shrooms, MDMA, and a sprinkle of ketamine, I became able to see my assault the same way I’d view it if it happened to a friend: with empathy instead of self-loathing.

The future looks hopeful with cities such as Denver and Oakland decriminalizing psilocybin and conducting trials on MDMA and ketamine for PTSD treatment. However, for now, if you’re a survivor considering psychedelics, remember how crucial setting and dosage are. If you’re not in a location where psychedelics are decriminalized, test your substances and ensure that you have a trusted friend with you while you trip –– and I wish you the same success that I’ve had.

All my experiences with psychedelics, from the meticulously planned to the spontaneous and ill-advised, have helped me reframe my assault. Able to separate the event from the body of hurt it left behind and the unruly actions it inspired, I could forgive myself. Better yet, I could begin to accept the obvious: it wasn’t my fault.