Christmastime, that magical moment each year when we sit around a warm fire sipping on cactus juice while singing “Rudolph, was a bright red mushroom.”

That’s not how your family does it?

The psychedelic origins of the Christmas mythology is one of those stories usually divided into two camps: psychedelics advocates swearing legitimacy and the rest of humanity shaking their head. Where myths originate and where they end up are often vastly different locations, however. Let’s explore the reasoning behind the idea that mistletoe and eggnog have more punch than you think.

Santa Origin Story

Santa Claus is a shaman who gives out psychedelic mushrooms as “gifts.”

If the origin story could be summated in one sentence, that might do. Of course, context is necessary.

The term “shaman” originates in Russia. The Tungusic term, šaman, is translated as “one who knows.” In his classical work on the topic, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, religious historian Mircea Eliade notes that many terms have been used globally to denote shamanic prowess: medicine man, sorcerer, magician. Eliade even speculates the shaman term is related to wandering mendicants, though that notion has been debated. As far as we know, shamanism etymology is particular to religious rituals in Siberia and Central Asia, which lines up with the Santa Claus myth.

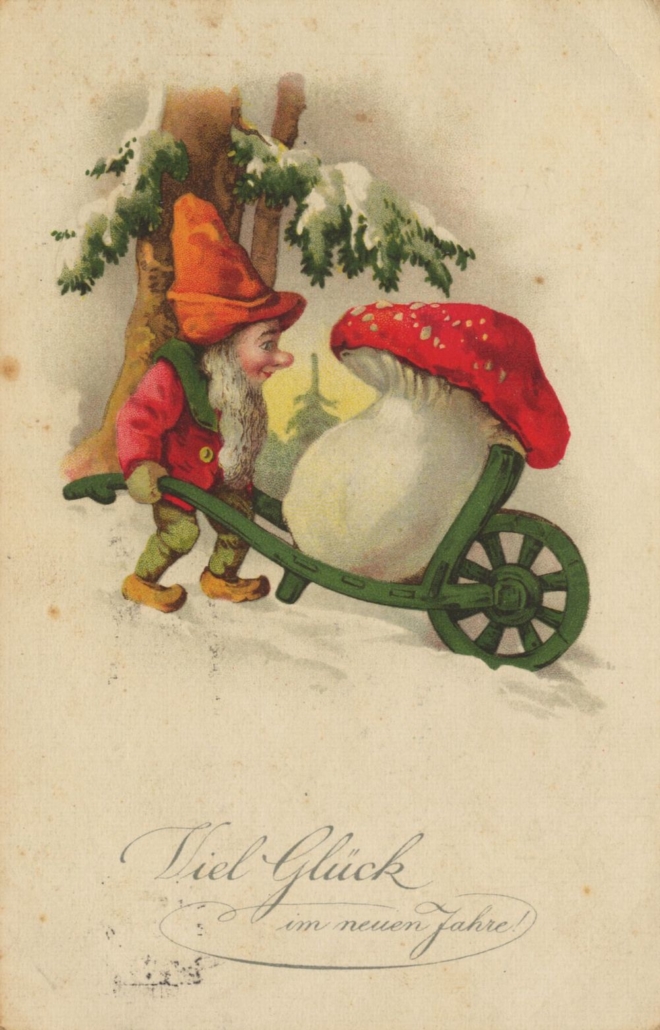

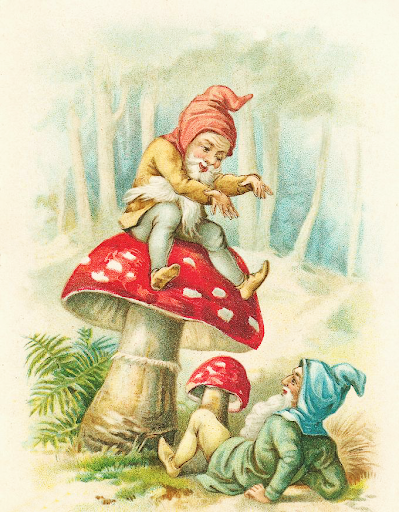

In fact, Santa’s famous red-and-white suit mimics the Amanita mushroom. Siberian shamans forged a close relationship with reindeer spirits, accounting for the magical “flight” that the North Pole resident makes every year—and, it should be noted, the North Pole lies in the Arctic Ocean, which buffers against the East Siberian Sea.

Those Magical Reindeer

Reindeer play a significant role in the shaman’s ability to travel. As Eliade notes, shamans take on a chimeric association with regional animals including wolves, bears, fish, and reindeer. The shaman “dies” to his old identity as he assumes this hybrid role, where the “animal symbolizes a real and direct connection with the beyond.”

This connection, as has been well documented, facilitates the “journey” shamans embark on thanks to a number of tools: holotropic breathwork, drumming, and psychedelics. If you’re going to visit all the children on the planet in a single night, you’re going to need a bit of magic.

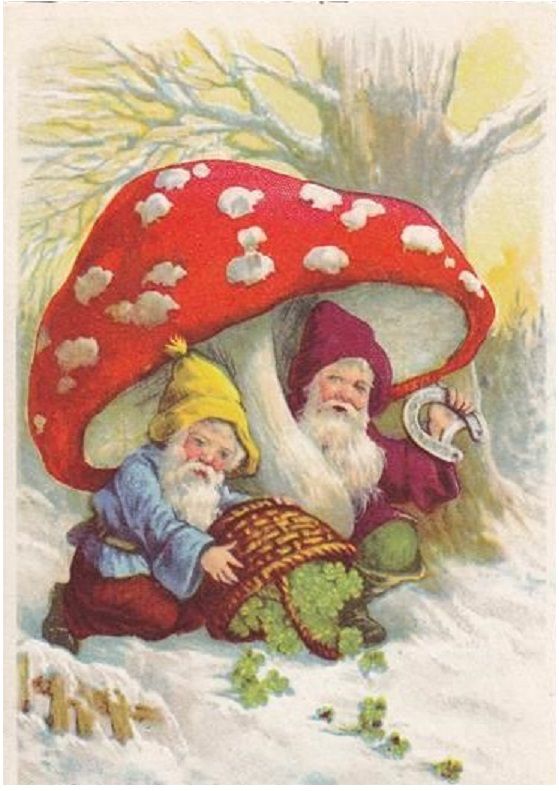

Reindeer actually eat Amanita mushrooms. They hunt for them in the wild. Science editor Andrew Haynes writes that humans trip on psychedelic mushrooms to feel a sensation of flight, and believes that reindeer seek them out to “escape the monotony of dreary long winters.” Like humans, they even appear to “have a desire for altered states of consciousness.”

Then there’s urine. Shamans and herdsmen are documented drinking reindeer urine in order to experience the psychedelic effects of the mushrooms the caribou have eaten. Incredibly, this isn’t only a cross-species phenomenon. Initiates drink the urine of shamans who have nibbled on mushrooms for the same reason. Psychedelic piss is known to be recycled up to five times, as evidenced in 18th-century reporting by Philip Johann von Strahlenberg.

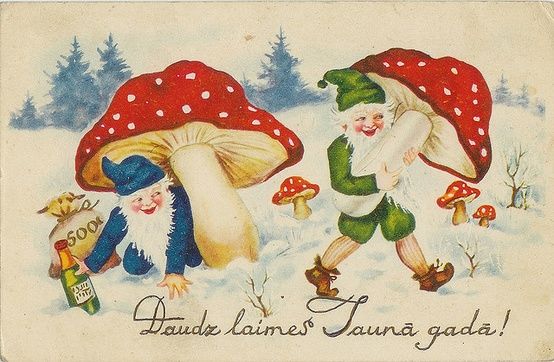

Mushroom Ornaments

Santa’s dress code and trusty flight companions aren’t the only connections to the psychedelic experience. Amanita mushrooms decorate yuletide iconography throughout Scandinavia and northern Europe. In fact, classics professor Carl Ruck has pointed out that Rudolph’s nose looks eerily similar to a bright-red mushroom.

While the practice of gift-giving during Christmas is relatively new—another hint of holiday capitalism is the connection between Santa’s dress code and the Coca Cola bottle —mushrooms are found underneath pine trees, just like holiday presents. In Mushrooms and Mankind, James Arthur points out the connection.

“Why do people bring pine trees into their houses at the winter solstice, placing brightly colored (red-and-white) packages under their boughs, as gifts to show their love for each other? It is because, underneath the pine bough is the exact location where one would find this ‘Most Sacred’ substance, the Amanita muscaria, in the wild.”

Anthropologist John Rush says this is more than a coincidence. In fact, the chimney symbology also finds a home in the snowy banks of northern shamanistic communities.

“As the story goes, up until a few hundred years ago, these practicing shamans or priests connected to the older traditions would collect Amanita muscaria (the Holy Mushroom), dry them and then give them as gifts on the winter solstice. Because snow is usually blocking doors, there was an opening in the roof through which people entered and exited, thus the chimney story.”

Since Amanita muscaria is poisonous, shamans dry them out on tree branches. These Santa prototypes were decorating trees long before we chopped them down and brought them into our living rooms.

Enter the Samis

Siberian shamans aren’t the only mushroom-eating medicine men. The Samis of Lapland in northern Finland also share stories about healing through gift-giving while drying psychedelic mushrooms on trees. As Matthew Salton writes in the NY Times,

“An all-knowing man who defies space and time? Flying reindeer? Reindeer-drawn sleds? Climbing down the chimney? The giving of gifts? The tales of the Sami shamans have it all.”

Regional connections shouldn’t surprise us. Wherever psychedelics appear in nature, rituals have emerged to celebrate them. As scholars like Eliade note, common motifs in medicine tribes include astral flight, healing powers, and trance states often associated with psychedelics. He writes secret societies being built around the notion of death and resurrection are a repeated historical phenomenon.

And what story better fits the mythos of Santa Claus, a man dressed like a psychedelic mushroom who is reborn every year, flying around the world bringing healing gifts to children, yet is never seen by a soul?