Depression can seem like an insurmountable mountain of sorrow and hopelessness to many people who experience it, yet its causes are far more complex than one might think.

Depression is a complex disorder whose onset has been tied to the outdated and contested monoamine theory. It is time to start looking at other possible theories that can explain what causes depression to develop better antidepressant therapies. Its adoption as the sole theory behind the pathophysiology (cause) of depression has stalled antidepressant research and fostered a pharmaceutical environment that made inefficacious therapies ridden with side effects become the norm in treating the disorder. The following is what the research states. All research is hyperlinked to its respective claim.

The Monoamine Theory

If I were to ask you what causes depression, what would you say? There’s a high chance that, like most people, you’d say that it’s brought on by some sort of imbalance of chemicals in the brain, a theory known as the monoamine theory. The monoamine theory has been the foundation for our current treatment approach with antidepressants, but how valid is it?

The monoamine theory states that the pathophysiology (cause) of depression is due to a deficiency in monoamine neurotransmitters (i.e. serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine). This was introduced after it was shown through clinical observations and animal experiments that the high blood pressure medication reserpine caused symptoms akin to depression due to it depleting neurotransmitters.

If depression was brought on by a depletion in neurotransmitters, then its symptoms would diminish after taking antidepressants, considering they increase neurotransmitter levels, yet this is not the case. In fact, the theory has been contested since its introduction in the 1950s due to the therapeutic lag that exists after taking an antidepressant. Antidepressants do increase neurotransmitter levels after acute administration, but no therapeutic effects occur until after chronic administration of the drug occurs. It can take weeks for someone to exhibit a change in their symptoms, and many times, antidepressants fail to work at all. Moreover, only about 40-60% of people notice an improvement in their symptoms within six to eight weeks after starting antidepressant therapy.

The Prozac Boom and How it Changed Everything

So how did this theory get accepted as the one to support current antidepressant use, if its validity has been questioned? Well, that’s thanks to The Prozac Boom of the 1980s and 1990s. Prozac was the world’s first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and its introduction in December of 1987 changed everything.

Actually, the world’s first SSRI was zimelidine in 1982. However, zimelidine caused Guillain-Barré syndrome. This is a syndrome where your immune system attacks the myelin sheath of your nerves which causes you to feel numbness, pain, and can sometimes develop into paralysis. Clearly, we can’t have that side effect, so Prozac was the world’s first relatively safe SSRI.

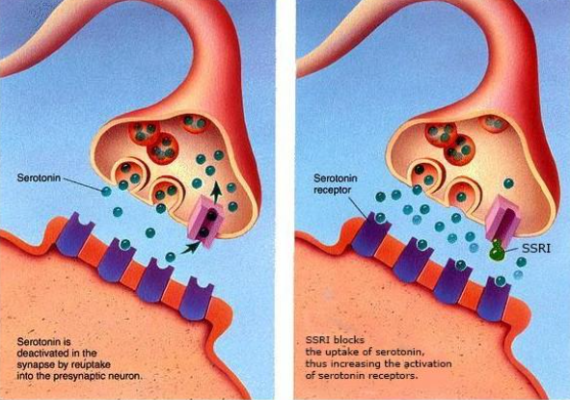

The mechanism of action of SSRIs relies on preventing serotonin from being reabsorbed into the presynaptic cells, thus increasing the amount of serotonin that remains in the synaptic space that then can send messages to the brain (Figure 1), therefore being considered a monoaminergic treatment. Prozac’s impact on society through its SSRI mechanism was significant and was touted as a breakthrough in psychiatry.

It is an understatement to say that Prozac was successful. Prozac completely changed psychiatry and the pharmaceutical world. In just three years after its introduction, it became the most prescribed drug in the United States, and four years later, became the second most prescribed drug in the world. The success of Prozac helped other antidepressants be developed and marketed, and by the end of the millennium, nearly 120 million people were on some sort of antidepressant.

Ever since the nascence of Prozac, SSRIs became the first line of treatment against depression. But the foundation of SSRIs is the monoamine theory, which as explained, has had its validity contested for decades. But surely there are better options? Well…not really.

All the current main antidepressant treatments (i.e. SSRIs, SNRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors) are all monoaminergic. In addition to their questionable efficacies, current antidepressants have less than stellar safety profiles. For example, side effects for SSRIs include: nausea, anxiety, irritability, insomnia, headaches, muscle spasms, agitation, tics, changes in appetite and weight fluctuation, diabetes, SIADH, gastrointestinal bleeding, hypomania or mania, serotonin syndrome, and irreversible Parkinsonism. Even with the issues in efficacy and safety that exist in SSRIs and other antidepressants, there hasn’t been any proper development in antidepressant therapies in decades.

Viewing depression through a monoaminergic lens has stalled research and it would be remiss of us to pretend that the financial success of Prozac and subsequent SSRIs didn’t slow down the development of better antidepressant therapies. Why would Big Pharma want to change pharmaceuticals that, even if foundationally broken, are making so much money? Continuing to adopt and work under a theory that time after time has shown to have limited applications in the understanding and treating of depressed patients sadly renders current interventions outdated and flawed.

Other Possible Theories of What Causes Depression

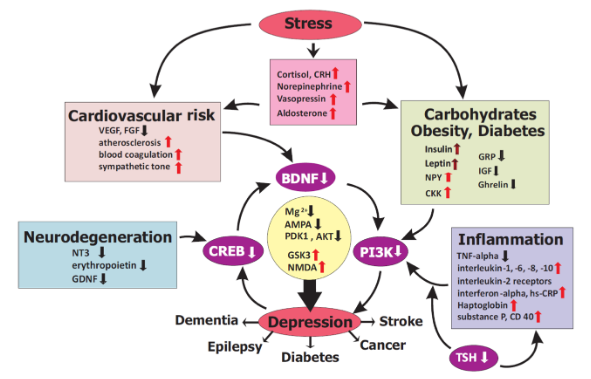

To treat depression correctly, a molecular basis of its onset needs to be understood, but that’s easier said than done. There is simply not just one thing that could cause depression; stress, cardiovascular risks, obesity, diabetes, inflammation, and neurodegeneration have all been attributed to the onset of depression via changes in the levels of specific molecules (Figure 2). I will discuss three of these theories: stress (HPA-axis disruption), inflammation, and metabolic causes.

HPA Axis Theory

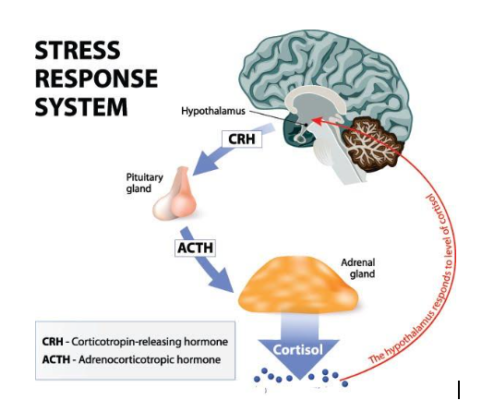

First, one of the main alternative theories of what causes depression is called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis theory, which in simpler terms means that chronic stress causes depression. The HPA axis is a complex system involving the communication between the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland in the brain with the adrenal glands found on top of the kidneys. This system is involved in reaction to stress as well as controlling other processes such as digestion, immunity, mood, energy, and sexuality, with a clear link having been shown between stress dysregulation and depression.

The HPA axis induces its effects through a multistep process that requires glands and hormones to communicate with each other. The hypothalamus releases two hormones (CRH and vasopressin) that stimulate the secretion of specific hormones (ACTH) from the pituitary gland, which in turn travel to the kidneys and prompt the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands to respond to stress.

If cortisol levels get too high, receptors in the hypothalamus and hippocampus help shut off the stress response through a negative feedback loop (Figure 3). This stimulation of HPA axis activity is normal and necessary to survive, but when hyperactivity of stress response occurs from being chronically exposed to high levels of stress, high levels of cortisol levels begin to be associated with negative effects like depression.

In a quantitative summary compiling four decades of research on the effects of cortisol on depression, increased cortisol production in depressed patients was evidently shown to exist. High levels of cortisol brought on by chronic stress has been shown to decrease a protein in the brain called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), whose decrease has been observed in depressed patients. Interestingly, chronic antidepressant use has been shown to increase levels of BDNF and play a role in reversing depressive states induced by elevated cortisol levels by fixing the disruption in the feedback loop occurring at the HPA axis.

This shows that a monoaminergic mechanism cannot be the sole reason for how the antidepressant functions: something else is at play.

Inflammation Theory

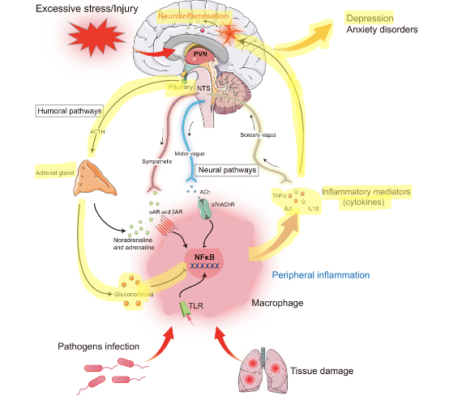

Inflammation has often been proposed as a promising mechanism of action of depression onset that directly dysregulates the HPA axis, too. Disruption occurs due to increased levels of cell signaling molecules called cytokines that activate pro-inflammatory responses. Three cytokines (i.e. IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-⍺) (Figure 4) have all been shown to be reliable biomarkers of inflammation-induced depression and are elevated in patients with depression and anxiety.

Antidepressant failure rates have also been shown to be affected by the presence of inflammation in patients. Interestingly, serotonin has been shown to activate pro-inflammatory responses when bound to a serotonin receptor and stimulated by serotonergic drugs like antidepressants. A hypothesis has been proposed that this can be explained that it could be possible that native serotonin levels may activate pro-inflammatory pathways, while other molecules cause a change of shape of the serotonin receptor that is able to activate different non-inflammatory pathways (142).

Metabolic Theory

Lastly, metabolic pathways have been proposed as causes for depression. While depression is often thought as a neurological disorder, metabolic systems have been proposed that are closely tied to hormonal dysregulations. Metabolic dysregulation and disturbances in glucose regulation has been proposed to be associated with the onset of depressive symptoms. Such an apparent key relationship between metabolism and depression exists that it has been suggested that depression be classified as metabolic syndrome type II.

The link between metabolism and depression seems to be due to gut-to-brain pathways controlled by different hormones. Leptin, a hormone responsible in inhibiting hunger and lowering fat storage, has been shown to reverse the dysfunction of the HPA axis and be involved in promoting hippocampal plasticity. Lack of said plasticity has been shown to have at hand at causing depressive states.

Ghrelin, a hormone primarily responsible for hunger, has been shown to have antidepressant effects when in circulation and dysregulating it can cause depressive symptoms. Under stress, the release of ghrelin has been shown to be stimulated and help enact antidepressant effects by interacting with the HPA-axis. Cholecystokinin, a fat and protein digesting-aiding hormone, has also been shown to induce depressive states through interaction withs the HPA axis by being released after exposure to chronic stress.

Current Research in Psychedelics as Possible Treatments of Depression

These are three theories that could help us better explain depression and be able to formulate better treatments. In fact, there have been some studies over psychedelics’ role in modulating these systems to explain their antidepressant qualities. One paper hypothesized that psychedelics directly repress the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules, therefore categorizing them as anti-inflammatory agents. Similarly, antidepressants have been shown to repress the expression of the pro-inflammatory molecule TNF-a. As aforementioned, the decrease of the molecule BDNF has been observed in depressed patients, but psychedelics have been shown to increase its expression – a possible tie in with the HPA axis theory. In addition to these studies, there has been a plethora of research regarding the viability of psychedelics as antidepressants. The research has also expanded to focus on the effects of synthetic, proprietary formulations of psychedelics, such as COMPASS Pathways’ study over single-dose synthetic psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression published in November 2022.

All in all, the current theory of what causes depression has been contested since its introduction in the 1950s. The current monoamine theory states that depression is brought on due to an imbalance of neurotransmitters in the brain (i.e. serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine). Antidepressants increase concentrations of neurotransmitters in the brain, but no therapeutic benefit occurs until after chronic administration, thus invalidating the monoamine theory.

The success of Prozac caused future drugs to remain bound to the monoamine theory and has severely stalled research and development of novel antidepressants. In order to treat depression successfully, we must stop thinking of depression as a monoaminergic disorder and be open to exploring other theories behind the pathophysiology of depression. Currently, three theories exist that seem to be intertwined that could explain the onset of depression better than the monoamine theory. These theories rely on seeing depression not as a neurological disorder, but rather a multi-system disorder that is highly sensitive to dysregulation of human stress, inflammation, and metabolic pathways. If we begin to rethink the pathophysiology of depression and how we treat it, society will be able to be given more efficient therapies with better safety profiles that are based on more probable theories.

Disclaimer:

This article is an adaptation of the author’s 2021 thesis for their Masters in Medicinal Chemistry titled A study of the antidepressant properties of psychedelics by way of 5-HT2A receptor agonism: insights into their therapeutic mechanisms of action and pharmacology.