The current psychedelic renaissance and the boom experienced by practices such as yoga, meditation, plant medicine, and the different forms of alternative therapy are the opening space for the growing spiritual tourism industry to expand even more in the next few years.

From the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon, where retreats offer carefully picked programs with exorbitant prices of $10,000 to the comfort of having psilocybin mushrooms with a private shaman in a hotel in Cancún, Westerners now fall into the risk of inadvertently perpetuating colonialism and cultural appropriation through spiritual tourism.

The topic is quite broad, involving a lot of dynamics and complexities that cannot be covered in one article. So, in this piece, I chose to highlight a few impacts that spiritual tourism has had on Mexico’s Mazatec indigenous culture, which is largely responsible for introducing the Western world to psilocybin mushrooms.

What Is Spiritual Tourism?

Spiritual tourism is a personal journey to a foreign destination, where one participates in activities with the intention of propelling spiritual growth. Although spiritual tourism is relatively new concept for many, in wake of more and more public figures sharing their adventures with plant medicine in exotic lands, it is not a new phenomenon. People from all over the world have embarked on self-discovery expeditions for thousands of years.

But the appropriation of practices born from philosophical and religious traditions of the East and Mesoamerica, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, or pre-Hispanic indigenous traditions, has its origin in the New Age hippie movement that emerged in California in the 1960s. The counter-cultural movement promoted environmentalism, spirituality, and the exploration of extraordinary states of consciousness. Gradually, these practices have been incorporated into the lifestyle of the Western world, leading to the flourishing of a global holistic wellness and spiritual industry.

Impacts of Spiritual Tourism on the Mazatec Indigenous Community

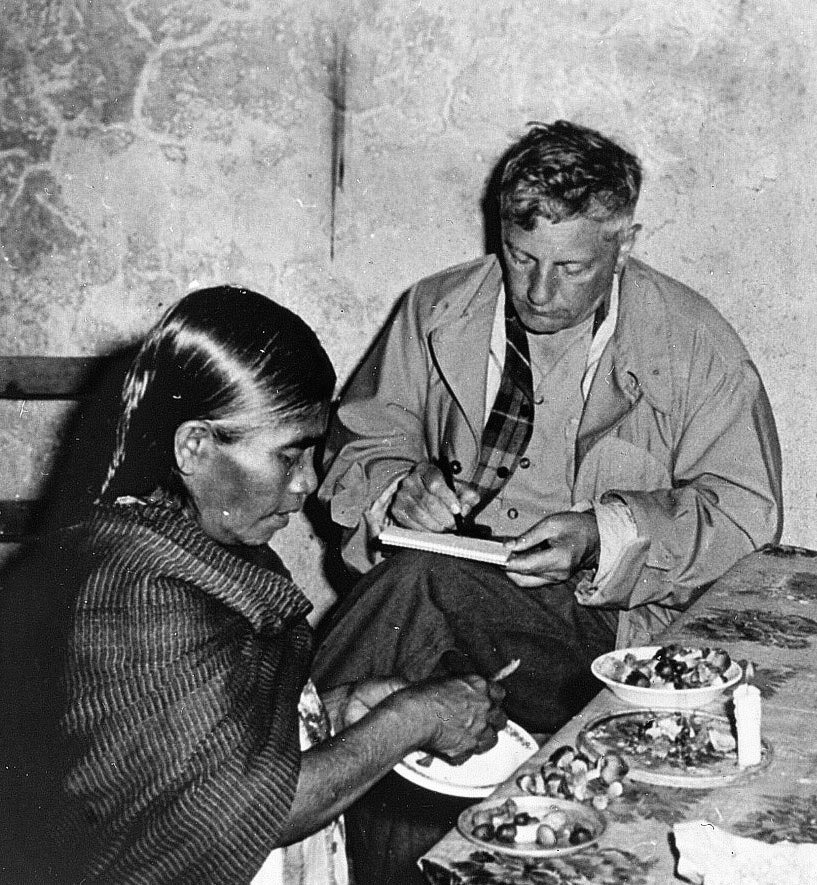

Gordon Wasson famously traveled to the small town of Huautla de Jiménez in Mexico in 1955. The banker, writer, and ethnomycologist participated in a psilocybin ceremony with Maria Sabina (both pictured above). His iconic article Seeking the Magic Mushroom was published in Life Magazine in 1957, and caused a flood of western seekers to descend upon Huautla.

The impacts of the spiritual tourism Wasson ignited can now be seen in the Mazatec’s relationship with their culture. There are now far more non-Indigenous people consuming psilocybin, holding ceremonies, and profiting from it than there are Indigenous. According to Indigenous Mazateco and anthropologist Gabriel Eduardo Estrada Martínez, the local community has actually become estranged from their own tradition.

“Talking with young people of the Mazatec community today, they mentioned that they do not find a purpose in the (psilocybin mushroom) ritual,” he writes in blog for the organization Students for Sensible Drug Policy. “They liken it to a pagan practice that no longer makes sense since the structure of the rite has changed. They consume restlessly without applying the rules that made it a spiritual practice.”

Sarai Piña Alcántara, a social anthropologist, points out another alarming trend: neoshamans. “The ceremonies began to be offered by what we call Indigenous neoshamans: men and women, some with a certain degree of traditional knowledge and others more improvised, who exclusively cater to tourists,” she says in an interview for the Chacruna Institute. “They combine Mazatec techniques and elements with some New Age practices.”

She points out that Mazatecs have reported being exploited by psychedelic “facilitators” coming to the region to learn from neoshamans, with the intention to offer plant ceremonies for profit outside the region.

Another relevant concern for Alcántara is the sustainability and conservation of psilocybin mushrooms in the region. Today, tourists can buy two types of mushrooms in the Sierra Mazateca, and many locals say it is extremely difficult to find them in the forest. “A commercial market for mushrooms has emerged since the 1970s, due to both tourist and Mazatec demand,” says Alcántara. “I also call attention to a constant shortage of mushrooms over the last nine years, caused by changes in land use and foreign demand.”

Researchers trekking to Mexico to learn about the magic mushroom pose a problem, too. “For a few years, some communities have reported that American mycologists have come to the area to do studies of various fungi, which range from tracking species to mapping their DNA,” she says. “This has been done without permission from the communities, without presenting research protocols, and without including the members of the communities in those studies.”

The power dynamic always seems to favor Westerners who come to extract sacred plant medicine, for one reason or another. Gordon Wasson’s classic trip to Huautla de Jiménez, for example, leads him to became a media star and an icon of Western psychedelics history. His host, however, had an extremely hard life afterward. Maria Sabina died in impoverished conditions in 1985, and to this day, still has not received due credit for introducing the magic of mushrooms to the Western world.

It’s important to remember that Indigenous peoples around the world are still fighting for survival, for the preservation of their cultural heritage, and sovereignty. They are subjected to daily violence, discrimination, and marginalization. The question is, how can Westerners continue to participate in plant medicine ceremonies without adding more stress on these communities?

Ethical Steps Forward

Spiritual tourists seeking out ethical ceremonies, and paying attention to the power dynamics involved before attending, is a great way to start.

Westerners looking to participate in plant medicine ceremonies should also research and educate themselves on Indigenous paradigms. Before traveling, evaluate the impact on that community: Is it beneficial, and if so, who benefits from it the most? Is the money going directly to the Indigenous people of that land? Is the retreat program developed to support the local community?

Reflecting on questions like these can foster mutual respect and understanding between spiritual tourists and the cultures hosting them. It is essential that we make historical reparations to these communities for appropriating mushroom medicine for Western science and industry. If we all make an effort through self-inquiry and reflection, better dynamics will flourish and exploitative practices will decline. Only then, we can truly grow spiritually.

To read more of Jessika Lagarde’s work covering psychedelics, visit Women on Psychedelics.