If you lived through the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s, you will remember a time when psychedelics represented the pinnacle of human potential. Philosophers and advocates like Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary were proclaiming that psychedelics would open the doors of perception, liberate the mind, and lead humanity into a boundless future fueled by the infinite possibilities of the imagination. With psychedelics like LSD, people now had the vision to dream up new ways of living in the world, invent new communal structures, and fabricate new religions to guide their beliefs. It was a time when the sky was the limit for humanity —the future seemed unbound from history.

So what happened?

When the psychedelic revolution crashed and burned at the end of the 1960s, the psychedelic vision of the infinite future died with it. A new wave of cynicism washed over a generation as the hippies were now seen as naive and backward, cloistering themselves into cults that guaranteed to unlock human potential but functioned more like brainwashing camps.

The psychedelic dream remained dormant for two decades until it was resurrected by the rave movement of the 1990s and Terence McKenna’s Archaic Revival. At the cusp of the digital revolution, psychedelic thought was reborn. The future once again seemed full of infinite possibilities. Shamanic lore of plant allies and spirit helpers mixed with science fiction visions of hyperspace aliens and mushroom spores from deep space. A new history was invented where every myth and religion was infused with undeniable psychedelic influence; psychedelic mushrooms were now responsible for human evolution itself; and the Mayan calendar could now predict the end of time in 2012. Psychedelics were the past, they were the future, they were the universe, and they would ultimately save the planet.

Things are very different now.

If you look at the bulk of psychedelic discourse today, you will notice that almost any talk of infinite potentials, spiritual awakenings, and sci-fi hyperspaces are almost totally gone from the conversation. The wild and woolly days of magical thinking have been replaced by the dry academic talk of using psychedelics to treat depression and trauma. The erudite psychedelic authors and intellectual pranksters have been replaced by bland and buffoonish ambassadors like Michael Pollan and Joe Rogan. Instead of lifting the veil and peering into the ineffable psychedelic mystery we are now talking about resetting the default mode network and microdosing to improve mood and increase worker productivity. Instead of discussing heroic dosing to receive telemetry from the galactic core, we are talking about removing the hallucinogenic properties from psychedelic drugs to make them more palatable for therapy.

For all of the talk about the infinite potential of the psychedelic future, the psychonauts of the past could have never predicted how dull and dreary psychedelic discourse would become in the 21st century. The archetype of the rabble rousing psychedelic guru has been sidelined and replaced by the research scientist delivering a PowerPoint presentation on clinical trial outcomes. Academics argue about schools of psychedelic therapy and inconclusive results due to blinding problems and placebo expectancy. Cohorts of PhD students are being trained to use questionnaires and scanning technology to find clinical evidence of a mystical experience for insurance purposes. Activists are fracturing over disputes in decriminalization efforts and arguing over who gets to control the psychedelic market once it’s deregulated.

How did the entire psychedelic field turn into a facsimile of a city council zoning meeting?

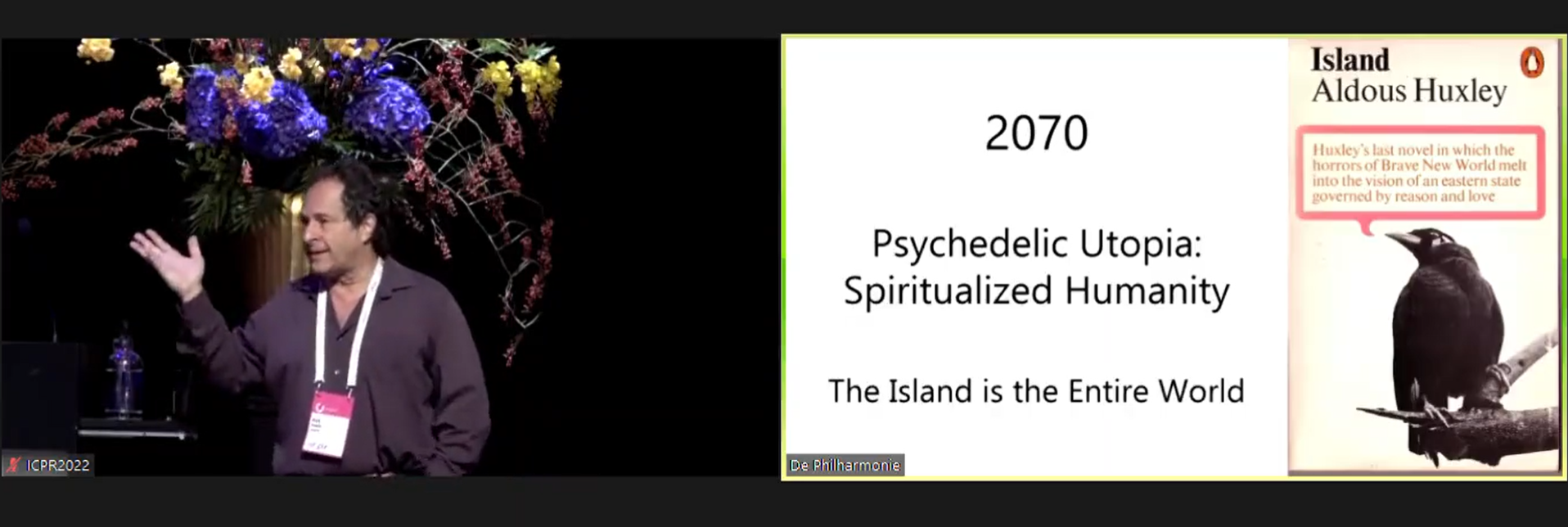

The new developers on the psychedelic block are still making blue-sky promises about the potential of psychedelics, but they are corporadelic VCs and CEOs who repeat the talking points “revolutionize mental health” and “magic bullet for depression” so often that the words become meaningless. And let’s not forget the one old-school holdout, MAPS Executive Director Rick Doblin, who is not afraid to approach the podium and make the outlandish claims that psychedelics will create a psychedelic utopia and “spiritualize humanity” by 2070. In addition to sounding like a desperate echo of the promises of the 1960s, Doblin’s claim of a psychedelic utopia also has obvious fascist and authoritarian overtones. In case Doblin has forgotten, historical efforts to “spiritualize humanity” have typically gone hand in hand with colonialism and genocidal oppression. Does anyone take this talk seriously? Why isn’t he laughed off the stage?

Perhaps the one thing that was most difficult for psychedelic prophets to predict was the one thing that was most inevitable: Money. The inescapable narrowing of psychedelic discourse can ultimately be attributed to the yoke of capitalism and the effort to legitimize psychedelics by making them profitable for corporations. The path to deregulation is a rat maze of legal hurdles and academic findings, all spun through hyped media coverage to influence public sentiment. This deregulation effort has led to an echo chamber of bland cognitive dissonance and a complete stultification of any imaginative discourse.

I am reminded of a time in the late 1990s and early 2000s when hemp activists were finally getting some traction in the media. During that era the public was inundated with facts about how hemp fabric would replace cotton and synthetic fibers, how hemp seed oil would become a sustainable biofuel, and how we would all be baking with hemp flour and eating hemp cheese. Hemp was going to take down big oil and end global warming and save the planet —with a single plant!

And if it wasn’t hemp activists talking about the world-saving power of hemp, there were the medical marijuana authorities who would repeatedly give the same speech about using marijuana to treat glaucoma, tremors, and AIDS wasting syndrome. All of these are important points, but take a moment to juxtapose the hemp PR campaign of the late 1990s with Cheech and Chong’s first movie, Up in Smoke, which premiered in 1978. How did all those hemp activists take something so light and fun —smoking weed— and turn it into such a bummer man?

There is a fairly easy formula to follow here. Capitalism requires deregulation, and the deregulation of drugs comes through a decades long public influence campaign. And for some reason the only way to influence public sentiment in favor of drugs is to make them seem as boring as possible. Ultimately, the medical marijuana activists were able to nudge public sentiment towards acceptance of cannabis, although this could also have been a generational shift attributed to people who grew up watching Cheech and Chong and perceiving pot as harmless fun. And though cannabis decriminalization has been successful in Canada and pockets of the U.S., it is still federally prohibited even for medical use, and hemp still has not replaced synthetic fabrics or made any significant inroads towards saving the planet.

It is interesting to note that in places where cannabis has become decriminalized for personal use, all talk of hemp fibers and treating glaucoma has disappeared. The vast majority of people who use cannabis have no interest in the talking points that were once the core of cannabis discourse. Now cannabis discourse trends more towards vapes versus gummies, pre-rolls versus classic joints, and more quotidian concerns like the best way to smoke weed out of a Monster Energy can —as it should be.

If we use history as our guide, it could be a long time before capitalism and deregulation allow psychedelic discourse to return to its natural state of imaginative play. The money has its own agenda and that is to figure out how to get paid and quibble over who controls the market and who reaps the benefits. That perpetual bland noise you hear about psychedelics in the media is the steam blowing off of this money churning process. And until this process burns itself out and the profits can be folded into the next bubble, it’s just talking points all the way down.