For decades, skepticism and restrictive drug laws have stalled research and acceptance for psychedelics within the scientific community — but the tides are beginning to turn. This fall, the University of Ottawa is leading the academic world in launching Canada’s first-ever psychedelic master’s degree program, marking a milestone moment in the movement for acceptance and normalization.

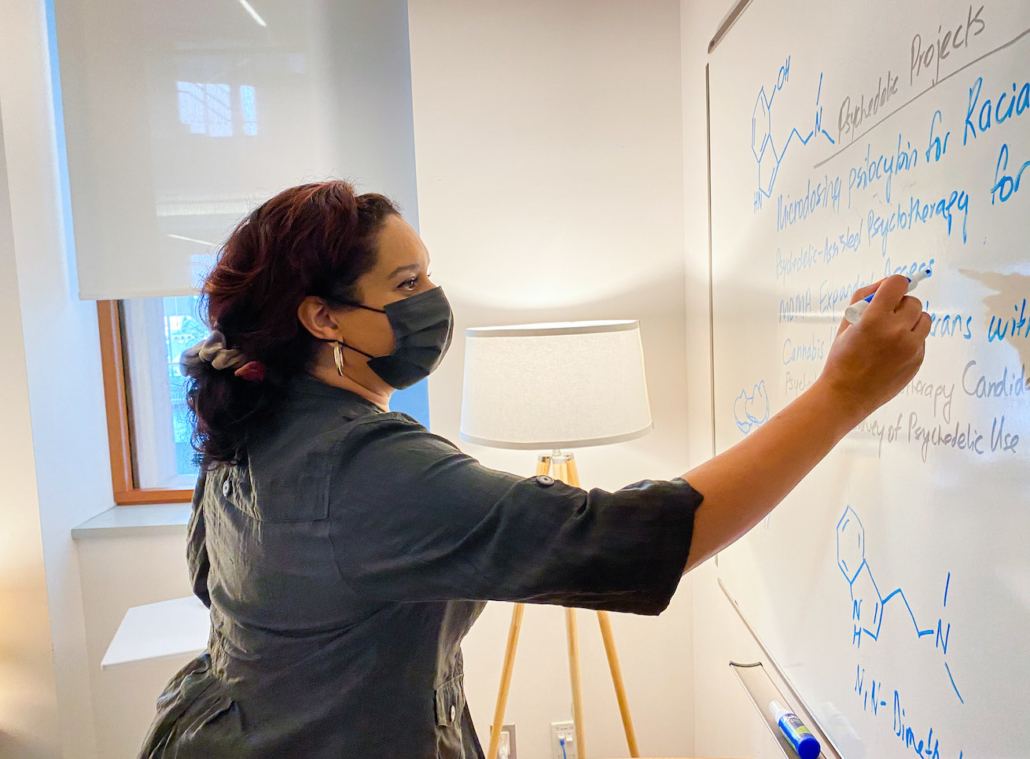

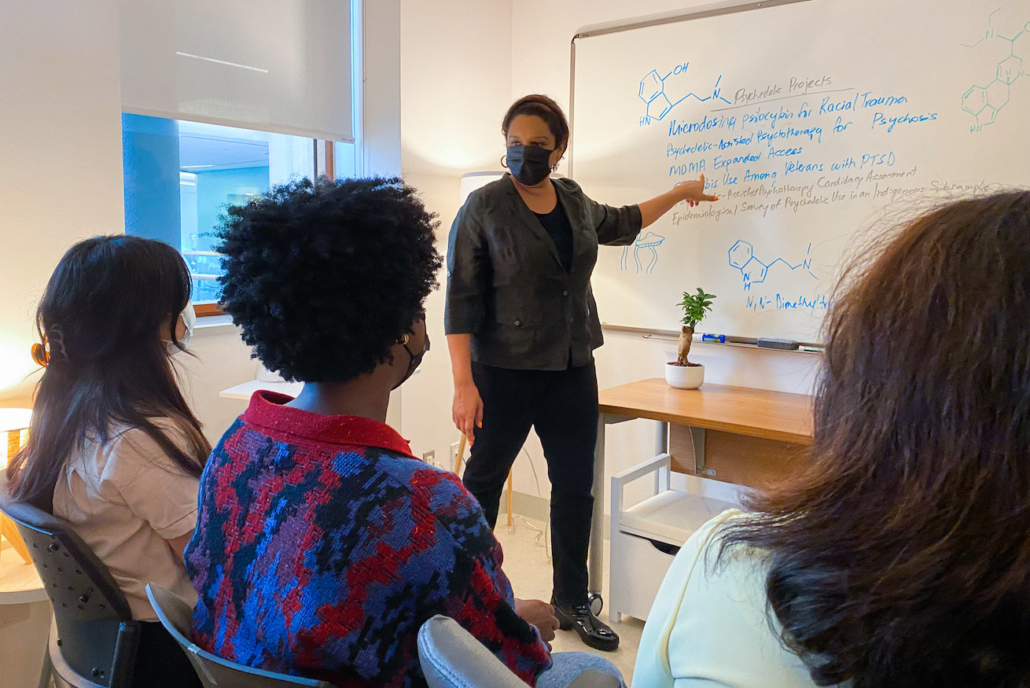

Developed by associate professors, clinical psychologist Dr. Monnica Williams and anthropologist Dr. Anne Vallely — the duo behind the school’s Psychedelic and Spirituality microprogram — this interdisciplinary graduate program weaves together elements of psychology, religion, anthropology, and neuroscience. The curriculum aims to prepare students for a near future where psychedelic-assisted therapy is a norm.

Of course, garnering support for psychedelic-focused education wasn’t easy — even with the seemingly ever-growing demand.

“I was getting emails almost on a daily basis from people who wanted to know how they could become psychedelic therapists,” Dr. Williams says. She referred students and practitioners to the California Institute for Integral Studies and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), but those requests underscored the need for a universally accredited academic program.

Unfortunately, her peers didn’t always agree.

“I thought about putting [a program] together when I was at the University of Connecticut. I brought it up many times at faculty meetings, but nobody took me seriously,” she says. “I think some people feel like, ‘What’s this weird hippie thing?’ or they remember Timothy Leary.”

The University of Connecticut also refused to allow Dr. Williams to use her research funds to attend a training in Costa Rica because it included a traditional ayahuasca ceremony — even though the training was legal and led by a well-respected anthropologist and medical doctor.

Luckily, when Dr. Williams began working at the University of Ottawa, things changed. There she met Dr. Vallely, who was interested in developing psychedelic education from a religious angle. They teamed up to present their ideas to their department heads, who green-lighted their microprogram and suggested developing a psychedelic master’s degree program. They received near-immediate support from arts and religious studies but faced some resistance from the clinical psychology department.

The opposition reflects a collective sentiment across the clinical psychology field, but the idea of using psychedelics to treat mental health disorders is nothing new. In fact, mid-century research on LSD showed tremendous potential as a treatment for alcoholism and addiction before the US and Canadian federal governments ruled all psychedelics illegal in the early 1970s. And although psychiatric interest blossomed again in the 1990s, advocates have continued to face backlash both inside and outside the scientific community, mostly due to outdated misconceptions.

But that could be changing, thanks to people like Dr. Williams and Dr. Vallely.

Today, there’s a fast-growing group of academics, researchers, and mental health professionals who recognize the need for education around psychedelics — particularly for practitioners treating conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). That’s because, without proper training, using psychedelics in therapy could pose risks.

Additionally, Dr. Williams believes it’s also essential to include diversity training in psychedelic studies (and all psychology programs in general). She has completed extensive research on how racism impacts people of color, as well as how people of color have been largely excluded from psychedelic research. The clinical psychologist recently appeared on Jada Pinkett Smith’s popular Red Table Talk series to advocate for equity of access to plant medicine, which the celebrity host said helped her recognize PTSD she was suffering from and overcome “crippling depression.”

“I think psychedelics can be a catalyst to cure racial trauma — but it can also cause more harm if your therapist doesn’t doesn’t know how to work with racial trauma,” she tells Psychedelic Spotlight. “That’s one of the reasons it’s important for this program to be one of the first. Other programs are going to look at our program as a benchmark, and if we have a cultural component embedded in it, I hope they’ll take their lead from that.”

After two long years of preparing documents, presenting to various committees, and earning buy-in from the clinical psychology team, Dr. Williams and Dr. Vallely’s program is in its final stages. The university will soon begin accepting applications for the fall semester and raising money for scholarships — especially for students of color. And, the microprogram, which is available now, includes classes that will count towards the master’s program.

Dr. Williams and Dr. Vallely’s work has paved a path for future university programs. Their program is launching the same semester as the UW-Madison master’s program for psychoactive pharmaceutical therapy, the first of its kind in the United States. Both of these could have an exciting ripple effect across the scientific community. But, there are likely many more hurdles to climb before psychedelic studies are fully accepted within academia.

For anyone considering developing their own psychedelic master’s degree program, Dr. Williams recommends having a team of allies and preparing for setbacks. “Knowing your stuff helps,” she says. “If somebody at a meeting says, ‘Well, is there a meta-analysis I can look at?’ I can say, ‘Yes, actually, here’s a meta-analysis that just came out last year.’”

In addition to educating critics and skeptics on recent research, she also says it’s helpful to share real stories. Like, for example, the multiple veterans with PTSD who, after years of suffering, finally found help by participating in MDMA and psilocybin studies and ayahuasca retreats in the Amazon.

“I think that’s something everybody can appreciate because these are people that put their lives on the line to defend our country. And now they’re suffering, and we have nothing more to offer them,” she says. “The fact that they’re able to find healing should make us all wake up.”